December. Number 336. Flower Garden And Pleasure Ground. Seasonable Hints

Description

This section is from the book "The Gardener's Monthly And Horticulturist V28", by Thomas Meehan. See also: Four-Season Harvest: Organic Vegetables from Your Home Garden All Year Long.

December. Number 336. Flower Garden And Pleasure Ground. Seasonable Hints

In making lawns it is more and more evident that discrimination should be used as to the kind of grass to be employed. Under the shade of trees, where it is not very shady, but is yet rather dry in summer time, there is nothing better than the sheep fescue grass, Festuca ovina. Under the same conditions, but more shady, the flat stemmed Blue grass, Poa compressa. In low ground, but not wet, the Bent grasses - species of Agrostis - are excellent, as they also are for ground subject to slight salt spray. Where the situation is not too wet and dry in summer or too cold in winter, Perennial Rye grass is very good; and for general purposes, outside of the other special cases, the Kentucky Blue grass, Poa pratensis, is best of all. For the long hot summers of the Southern Atlantic States no first-class lawn grass is known; the Bermuda grass we believe is the only one that will at all keep a green smooth face during summer, but this one will not bear close mowing. If any better has been found, it is not yet generally known. In sowing seed in the fall, in the North where young grass plants may be drawn out during a thaw, it is usual to sow wheat or rye with the grass seed. The comparatively heavy leaves fall on the small grass plants and keep them in the earth.

There is no other use for wheat or rye, and it should not therefore be sown on a spring-made lawn. The grass seed should be sown as early in spring as it is practicable to work the ground. Very well rotted manure or some fertilizer is excellent to fasten the setting of the lawn. Clover should never on any account be sown with grass seeds for lawns, nor should any other creeping thing that will dispute with the grass the right to exist. Weeds of any kind that are likely to seed should be drawn out by hand or trowel. Few things pay better than to keep a lawn weeded during the first year of seeding. Towards fall inequalities may be noted over the surface. The lower places may have fine earth spread over, neatly raked, and rolled over when dry. The grass plants will come through the following spring. The result will be a lawn of which one may be proud. Where it is difficult to get grass seed to grow well sodding has to be resorted to. It is not easy to get laborers to do this well, except near large cities where the men have more practice.

As a general rule seeding will make a better lawn, if we can afford to wait a year to get it.

In trimming hedges the shears seldom get down to the plane of the year before. For this reason the hedge often becomes in time higher or wider than is desirable. In deciduous hedges this may be remedied by cutting back to the ground at this season. When spring comes a thick mass of sprouts will push out which can be nipped into shape as the season grows. The hedge, as most people know by this time, should be wider at bottom than at top, so that the leaves may all get as much advantage from light as possible. The more shade at bottom, the sooner the hedge gets thin at the base. The beauty and effectiveness of a hedge is, to be as vigorous at the bottom as at the top. For deciduous hedges there are the English and American Beeches, English and American Hornbeam, Pyrus Japonica, Chinese and American Privet, Silver Thorn or Elaeagnus, Buckthorn, Osage orange, Honey Locust and Berberry. These have been well tried and are in general use. But since the introduction of barbed wire a greater variety of shrubs may be employed for deciduous hedges. Two or three strands of barbed wire may be stretched on temporary stakes over the hedge, and the plants growing through the wire will sustain them when the posts rot away.

This in a measure supplies the thorns the shrubs may be deficient in, and makes the protection the the plants alone could not give.

In managing hedges do not begin trimming too early. The old fallacy that pruning strengthens plants has been wholly exploded. It weakens plants; is, in fact, a severe blow to their vital power. Strong shoots appear after pruning certainly, because they get food for themselves that was intended for scores of others as well. It is therefore not wise to trim a young hedge at all for several years. Take an Osage or Honey Locust, strong growing plants, for instance; let them grow as they will for two or three seasons, according to the thickness of their stems; when they are, say 2 inches thick, saw them to the ground at this season. Then the numerous strong shoots that will push up the following year will make a complete thick hedge 4 feet high in one season. Where the barbed wire is to be employed as a strengthener to a weak kind of plant it may not be put up till this cutting down of strong plants for the final benefit of the hedge is resorted to.

Evergreen hedges, unfortunately, can not be cut down when they become too large. They will not sprout from the base. The only safeguard against getting too large is to keep them cut rather lower than we should want them ultimately to become, so as to provide for the future accretions. The barbed wire lines for the plants to grow through are very useful in evergreen hedges. They are seldom used for protective fences because cattle and unruly boys can easily break through. But with the barbed wire we may have protection with their winter beauty.

Chinese and American Arbor Vitae, Norway Spruce, Hemlock Spruce, Scotch Pine, White Pine, and in some cases Red Cedar, are the usual plants for hedges north of the Potomac; or south, in the elevated regions where the frost is absent or light, the broad leaved evergreens are employed. The Japan Euonymus is one of the best, though Pit-tosporums, Gardenias, Oleanders, Chinese Tea, and similar plants are often employed very effectively.

In arranging for the beauty of one's garden there is more art in deciding the location for the trees than in anything else. Indeed it is here generally that the most important part of the art of the landscape gardener comes in. In some places the trees are set with almost mathematical precision, each at any rate by itself. There is much in the beauty of single trees, and to lead us to desire that no part of the branches are to be interfered with by those of another; but we cannot do without groups or clumps, where it is a matter of little consequence what becomes of the lower branches in the interior of the mass. Then masses divide views, which is one of the chief efforts of the landscape gardener. If we see the building all at once, it seems the same house no matter how we may wander around it, but when every view of a dwelling is flanked by its own separate set of groups distinct pictures are presented that one may almost believe he has a dozen mansions instead of one.

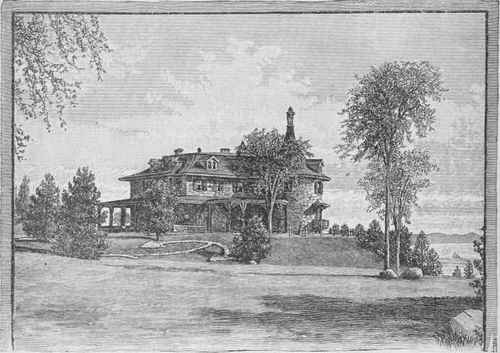

Ridgeview, Irvington-on-Hudson. Residence of Mr. A. C. Richards.

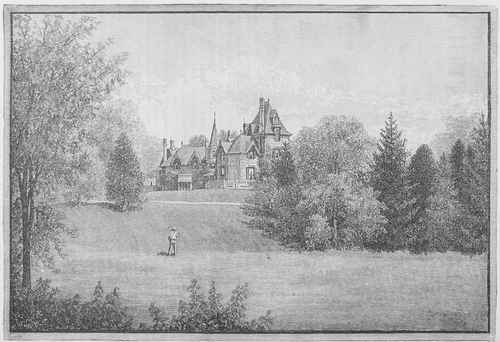

Residence of William Barton, Irvington-on-Hudson, N. Y.

In illustration of these admirable principles in landscape gardening, we give on opposite page an illustration of the residence and grounds of Wm. Barton, Esq., Irvingtonon-the-Hudson, N. Y. We see here the beauty of the single tree, the open lawn with glimpse of the house, the group of trees concealing part of the house, and we can readily comprehend how different the view of that house would be if we were on the other side of the group, as we are when on the main drive.

What is true of the large mansion is true of the humblest residence where there is any room for gardening. We use there small growing plants - shrubs - for groups, instead of trees. The writer has seen grounds of not over a quarter of an acre given an inexpressible beauty few could imagine by a little art in the arrangement of trees and shrubs.

Continue to: