I. Passive Movement

Description

This section is from the book "Massage Its Principles And Practice", by James B. Mennell. Also available from Amazon: Massage It's Principles and Practice.

I. Passive Movement

Many masseurs seem to think that when passive movement is ordered it is their duty to move the part through the widest range that anatomical considerations will allow. Nothing could be a greater delusion, as usually the prescriber wishes only a minute movement to be given the first day, with small additions day by day as the condition improves. To be truly passive the movement must be carried through by the operator without either assistance or resistance from the patient. Unless the part is completely paralysed this entails the co-operation of the patient. It is difficult to allow any part of the body to become absolutely relaxed, and particularly so when that part is being moved. It is possible: but it is often necessary to teach patients how to do it, and this may require much time and patience. Without the co-operation of the patient in this active relaxation, passive movement is inconceivable, as, in its absence, the movement becomes either an assistive or a resistive movement.

I have found it so difficult to impress on those working for me that the patient's co-operation is essential to the administration of true passive movement that I have abandoned the use of this term altogether and adopted that of "relaxed movement."

The difficulty in securing active relaxation is so great that attention to every minute detail, which may be helpful, is imperative.

The first essential is that the patient should be in a position of absolute ease and comfort, in one of the natural positions of perfect repose.

The second is that the masseur should be in a position which renders it possible to support the part under manipulation in such a manner that throughout the movement, no matter what it may be, the patient still maintains the full sense of ease and repose. To secure this the masseur's movements must be so free from embarrassment that the sensation of absolute security is conveyed to the patient. The faintest trace of insecurity will be countered by the voluntary or involuntary contraction of the patient's muscles.

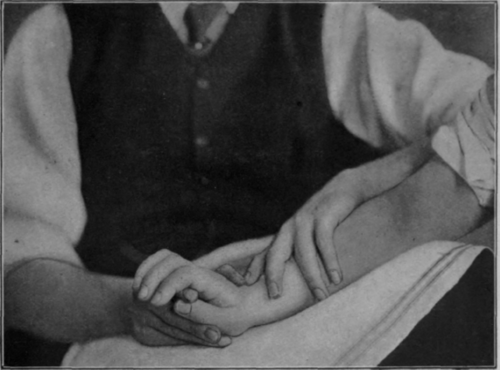

Fig. i6. - To show flexion of fingers with extension of the wrist.

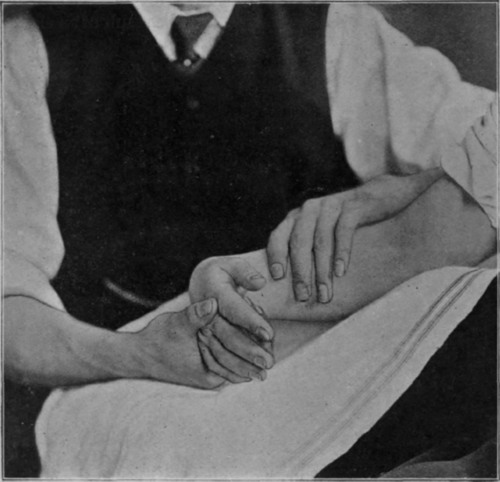

Fig. 17. - To show extension of fingers with flexion of the wrist.

The third essential is that the masseur should bear in mind the natural positions of repose, and should remember how the patient would perform the movement prescribed were he to do so voluntarily in the position chosen.

Nature has decreed that most of our movements should be in reality a combination of movements, the result of an elaborate co-ordination of muscular contraction and relaxation. If we wish our patient to maintain a condition of active relaxation, it is essential to copy, so far as lies in our power, the movements that result from this co-ordination.

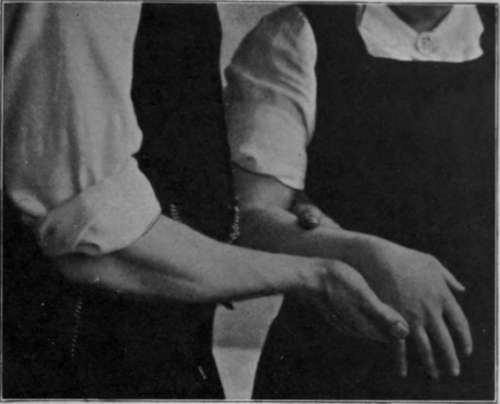

Fig. i8. - Showing the position in full extension of the wrist. The forearm is pronated and fingers are flexed.

The following list will serve as a guide; the combinations must be duly regarded whichever of the two or more movements constitute our chief aim. Moreover, for our technique to be perfect, it may be necessary to perform two or more combinations at the same time: -

Flexion of the fingers should be combined with extension of the wrist: extension of the fingers with flexion of the wrist (see Figs. 16 and 17).

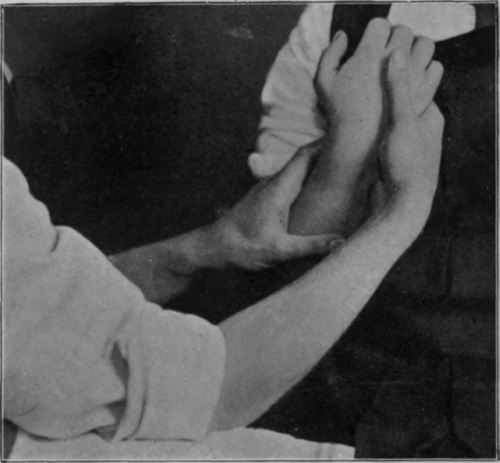

Extension of the wrist should be combined with pronation of the forearm (see Fig. 18): flexion of the wrist should be administered as the forearm movement passes from full pronation to a position mid-way between pronation and supination (see Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. - Showing full flexion of the wrist. Note the rotation of the forearm as compared with Fig. 18, and also the unaided extension of the fingers.

Lateralisation of the wrist in both directions can be performed in this position, but it is safer to begin with ulnar deviation and to pronate the forearm slightly while performing the radial movement (see Figs. 20 and 21).

All relaxed movements of the wrist and rotation of the forearm can be performed with the patient recumbent and the forearm vertical. The posterior surface of the arm should rest on the couch (see Fig. 41, p. 88). Adequate support is essential during flexion and extension of the wrist in this position. In the upright position supination of the forearm should be combined with flexion of the elbow: pronation with its extension (see Figs. 22, 23, and 24).

Fig. 20. - To show ulnar deviation of wrist.

Fig. 21. - To show radial deviation of wrist. Note slight relative pronation.

Fig. 22. - To show full supination of forearm with flexion of elbow.

Continue to: