The Influence Of An Excessive Meat Diet On Growth And Nutrition. Part 4

Description

This section is from the book "Food And Feeding In Health And Disease", by Chalmers Watson. Also available from Amazon: Food and Feeding in Health and Disease.

The Influence Of An Excessive Meat Diet On Growth And Nutrition. Part 4

B. In The Second Generation

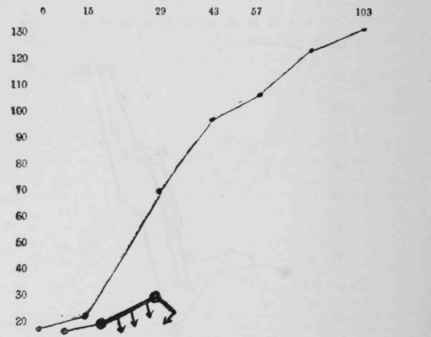

The recuperative power in the second generation of meat-fed rats was tested in four animals taken from two litters, other four animals from the same litters being employed as controls. After weaning, the eight were kept on a horse-flesh diet for two weeks ; in this period their weight was little more than maintained (see Chart 8). Two from each litter were then transferred to a bread and skimmed milk dietary, the remaining four being kept on the horse-flesh diet. All four meat-fed subjects succumbed in two to three weeks, the four transferred rats living and gaining in weight in the striking manner shown on the chart. The later history of these four rats is of great interest. The animals were killed when eight months old, their average weight being 150 grammes. Their health during the later months was very defective, the symptoms manifested being, in order of onset and severity, (a) accelerated and noisy respirations, dry rales being audible a considerable distance from the hutch; and (0) a dry condition of the skin, with roughness and loss of hair. These clinical features considered alongside of the other facts recorded in this paper point to the general conclusion that the symptoms from which the animals suffered in later life were etiologically related to the use of the defective dietary in very early life. There can, it appears to me, be no reasonable doubt that the symptoms observed were the result of the premature loss of some vital function or functions, and more especially of those concerned in warding off bacterial infection from the respiratory, and probably also the alimentary, tract.

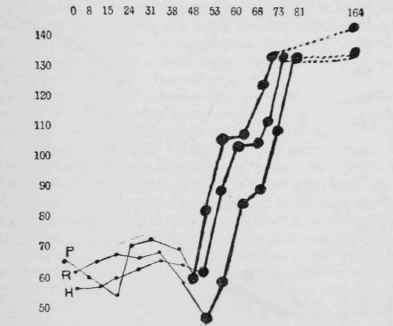

Chart 7. The influence of a bread and skimmed milk diet on young rats previously fed on an abnormal dietary. The curves represent the weight of three young rats that were fed on porridge, rice, and horse-flesh respectively for six weeks, and were then (forty-eighth day) transferred to a bread and skimmed milk diet.

Summary Of Results

These experiments prove that the excessive use of a meat diet in rats is attended with the following results : (1) growth is retarded; (2) sterility is induced if the diet is commenced in very early life; (3) the power of lactation is diminished; (4) a permanent weakening of the resisting power of the animals is induced by the use of an excessive meat diet in early life, the animals succumbing to disease at an unusually early age; and (5) there is a high death-rate in the offspring of animals fed on an excessive meat diet.

Chart 8. Recuperative power in second generation of meat-fad rats. The faint line equals the average weight of four rate bred on an ox-flesh diet which were transferred to a bread and skimmed milk diet at the age of six weeks. The dark line equals the avenge weight of four rats from the game litters which were not transferred but were kept on the meat diet.

Commentary

The facts recorded have an interesting bearing on the two questions of physical deterioration and high infantile mortality that are engaging medical attention at the present time. With regard to these conditions there is no doubt that not one but several factors are concerned in their production. There is equally little doubt that among these factors the question of diet occupies a foremost place. The defects in a diet may lie in one of several directions. The food may be of fair nutritive value but insufficient in amount; on the other hand, it may be of high nutritive value, excessive in amount, and of a nature which exercises an injurious effect on the organs and tissues. It is important that some light on this subject should be looked for from experimental medicine, and in view of the increasing prevalence of the consumption of animal food in this country it is of special importance to determine the effects on the organism of an excess of animal protein food. The main interest of my experimental results lies in the clear evidence submitted that an excessive meat diet can itself induce in animals - whose dietetic habits are fairly akin to those of man - some of the most prominent symptoms of physical deterioration - viz., defective general physique, deficient power of lactation, diminished fertility, and a high infantile mortality. I believe that these symptoms are, to an important extent, comparable to those prevailing in the human subject at the present time, the symptoms in man having, however, been established in a more gradual manner, their onset being contributed to by the operation of other etiological factors.

Some points of practical importance are brought out in the record. Of these the most noteworthy is the importance of a proper dietary in very early life. My experiments showed that the use of an excessive meat regime in early life induced a serious and permanent weakness of the animals, which, however, remained for a long time latent after the substitution of a physiological dietary. Clinical experience has led me to think that we have here also a close parallel in diseases in the human subject, and more especially in the class of affections commonly included under the terms gout and goutiness. Be that as it may, the experimental results indicate the importance of directing particular attention to the early dietetic history of patients so far as these are obtainable. The necessity for this will be further emphasised by the subsequent records of the structural changes in the organs and tissues observed in the course of these experiments.

Continue to: