Coffers And Chests From The Norman Times To The Renaissance. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "Old Oak Furniture", by Fred Roe. Also available from Amazon: Old Oak Furniture.

Coffers And Chests From The Norman Times To The Renaissance. Part 3

The English tilting-chest which we have in the vestry of York Minster is actually a much finer specimen than either of these French coffers, and still retains traces of its original colouring and gilding. This piece deserves most careful study by all those interested in the art of the Middle Ages. The representations of the various phases of St. George's encounter with the dragon carved upon the front are executed in a remarkably spirited manner, the culminating-point of the decoration being the huge curved form of the stricken monster which appears beneath the lock-plate.

Though possessing striking similarities to the Dublin and South Kensington coffer fronts representing the same legend, this magnificent piece of work, which is evidently by the same master-hand, shows much greater power of design. Forgeries of such coffers as we have just treated of are not unknown, but though most of the veritable specimens are known and located, it can hardly be said that it would be impossible to discover fresh examples. M. Peyre, who lived to our own time, acquired the curious little Gothic coffret carved with tilting knights, which was purchased with the rest of his collection for the nation, and may now be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

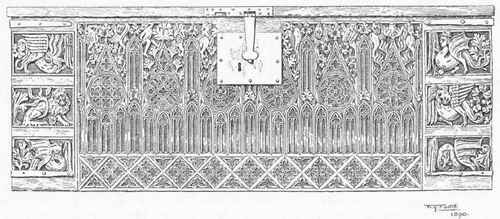

CARVED OAK COFFER OF THE PERPENDICULAR PERIOD IN BRANCEPETH CHURCH, NORTHUMBERLAND.

During the Perpendicular period coffers still continued to be made, though English productions of the fifteenth century are exceedingly scarce. Indeed, traceried boxes of national work of that period are almost as rare as the so-called tilting coffers, of which we have just given an outline. The chief reasons for this rarity have already been explained. The 'strangers artificers,' as they were then termed in the latter part of the fifteenth century, made their ex-portations to this country so seriously felt that Richard III., partly to popularize himself, no doubt, passed, in 1483, an Act prohibiting the importation of furniture of foreign workmanship under severe pains and penalties. Good specimens of coffers of the Perpendicular period exist in Brancepeth Church, Northumberland, and St. Michael's Church, Coventry, while foreign examples of the same date can be seen in the churches of Minehead, Somerset, and Southwold, Suffolk.

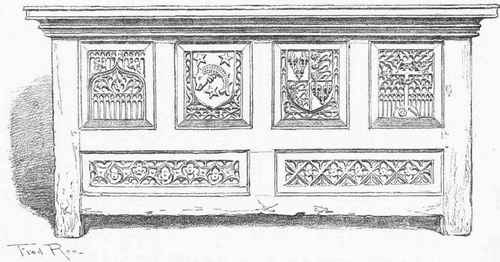

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY FLEMISH HUTCH IN MINEHEAD CHURCH, SOMERSETSHIRE.

A very beautiful 'Flanders chest' was formerly in the church at Guestling, Sussex, but it has gone the same road as many other fine relics of the same nature, and the visitor to Guestling may search for it in vain. An excellent wood-cut in Parker's 'Glossary of Architecture' will give him a good idea of the appearance of this ornate piece.

Though 'Flanders chests' were freely imported during the fifteenth century, we must not necessarily attribute to every specimen which bears a flamboyant twist in its tracery a Continental origin: English east coast productions of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries often approached foreign designs in mannerism. Home manufactures may, however, usually be detected by greater boldness in their design and handling.

It is singular that so many fine early coffers should be found in an area which, roughly speaking, comprises the eastern fringe of England. Most of their characteristics are too intensely national to admit of a suspicion that these coffers were imported from abroad, but it may be that a freer intercourse with Continental traders, and the educational influence which contact with skilled foreign labour promoted, tended to foster high-class production in this quarter. In medieval manuscripts and inventories we frequently come across the words 'trussing chests,' or 'standards,' these being the contemporary names for large strong-boxes which were used for the purpose of transporting weighty articles. It will be noticed that some of the medieval coffers are provided at each end with large rings, which are sometimes dependent from chains or bars of iron. When required for journeys a pole would be passed through these rings, and the chest would thus be slung across the backs of two mules. This feature may be seen amongst other examples in the treasure-chests which still exist in the Chapel of the Pyx at Westminster. At Chichester, too, there used formerly to be an early chest having ends clamped in the form of a grille and fitted with transport rings of this description.

This interesting relic appeared to be locally an unconsidered trifle, and was not treated with the care that it deserved.

It was one of the most usual things for the cofferer of the Middle Ages to collaborate with the smith, and many splendid examples still remain to testify to the success attending their joint efforts. There are two semicircular cope-chests at York Minster strapped about with a sinuous entanglement of iron scrollwork in which the summit of elaboration may be said to have been reached. One of these monsters is actually covered next the wood with an outer skin of cuir bouilli to further protect its precious contents. Both of these examples probably date from late in the thirteenth century. Sometimes, as we have seen in the case of the Newport relic, the construction of the coffer became triple-barrelled, in which each craftsman played his part. A remarkable coffer, which was formerly in the Court of Chancery at Durham, but is now in private hands, is an example of this kind. It is formed of massive slabs of oak, bound together with bands of wrought-iron terminating in double splays, the inner surface of the lid being painted in tempera with a mythical subject representing a combat between an armed centaur and the enemy of man.

Continue to: