Table Glass. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "Hints On Household Taste In Furniture, Upholstery And Other Details", by Charles L. Eastlake. Also available from Amazon: Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details.

Table Glass. Part 3

In the days of the Venetian Republic, its glass was exported to every country in Europe. Its manufacturers were artists who vied with each other in the beauty of form and the fertility of invention which their designs expressed. Not many years ago this national art had degenerated into a trade which produced little more than glass beads and apothecaries' bottles. It has, however, lately been revived through the exertions of Dr. Salviati, himself a Venetian, but whose name is well known in this country in connection with the enamel mosaics which are now extensively used as a means of architectural decoration. But no design, however beautiful in itself, could have been carried out, but for the intelligence and ability of the Venetian artisans and the glass manufacturers of Murano. Many of these men were struggling in a state of poverty, for the work on which they had for many years past been employed was of the humblest description, and for this work they received the humblest wages.

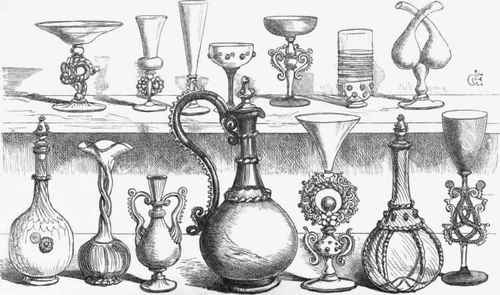

The demand of the last two generations for the produce of their ancient handicraft had been so unimportant that these honest folks were reduced to earn a livelihood by plying the meanest and worst-paid branches of their trade. One of them, an ingenious native artisan, first suggested the possibility of reproducing the almost forgotten manufacture of enamel mosaics. Aided by this man's practical experience, Dr. Salviati, who himself possessed the zeal and taste of an able connoisseur, undertook a series of experiments, which resulted in the establishment of his well-known factory at Venice; and we need only refer to the mosaic decorations of St. Paul's, of the Wolsey Chapel at Windsor, to those executed for the Albert Memorial and for the altar-piece at Westminster Abbey, to prove that the revival of so venerable and splendid an art is well appreciated in this country. But Dr. Salviati has done more for Venice. Encouraged by the advice of some English artist friends, he has endeavoured to reestablish there a manufactory of table glass, which, in quality of material, excellence of design, and spirit of workmanship, promises to vie with anything of the kind which has gone before. Indeed, there seems little reason why it should fall short of former excellence. In England, the great difficulty of bringing about such a revival would probably be the want of skill in the art-workman. But at Murano these poor glass-blowers appear to inherit as a kind of birthright the technical skill in a trade which made their forefathers famous. Better wages, a more interesting occupation than they formerly enjoyed, and, may be, a feeling of national pride which recent events have awakened, combine to encourage their efforts. Dr. Salviati has done his best to procure good designs (some of which have been furnished by Mr. Norman Shaw), and old examples for the men to copy. A large depot for the table glass, under the management of an English company, aided by the zealous exertions and valuable advice of Mr. A. H. Layard, is now opened in St. James's Street; and considering how short a time has elapsed since the first attempt was made, the specimens which have reached England are remarkably good. Here may be seen, in rich variety of form and colour, water-bottles, claret jugs, tumblers, wine and liqueur glasses, salt-cellars, preserve jars, flower stands, tazze, vases, etc. etc, many of them very beautiful in design, and all possessing qualities of material which we may seek in vain among our English goods. They have not, indeed, the cold accuracy of form and spotless sheen of an ordinary dessert service, but they are far more picturesque in appearance, wonderfully light in weight, and cheap enough to bear competition with any table glass which has pretensions to artistic merit. Some of the goblets are highly decorated below the bowl with bosses of coloured glass, conventionally-shaped flowers, and that peculiar kind of pinched-up ornament to which the Italians give the technical name morise. The term ritorto is applied to a delicately-striped glass, which is frequently made into lily-shaped bowls and dishes.

Specimens of Modern Venetian Table Glass, manufactured by Sal-viati & Co.

Another very beautiful kind of ware is produced by joining two thin films of glass in such a manner as to leave air-bubbles distributed in a sort of diapered pattern over its surface. This is called 'bubble filagree,' and is much prized on account of the delicacy required in its manufacture.

The old Dutch type of water-bottle, with its round capacious bowl of thin glass, strengthened at intervals with little twisted ribs of the same material, was manufactured in ancient Venice also, and frequently decorated with colour. It is now produced at the price of a common wine decanter. In like manner the sturdy green hock glasses which we once imported from Holland have been imitated and improved on by Salviati; for whereas their broad-ribbed stems were not unfrequently cast or blown into a mould, those just sent over from Venice have stems composed of an actual cord of glass wound spirally round, and so spreading outwards to form a foot. When the avventurino decoration is introduced in this type of stem its appearance is very beautiful. The principal colours used are bottle-green, turchino, ruby, amber, olive, and acquamarina - a very pretty sea-blue tint, which is peculiarly characteristic of this glass. Some of the smaller tumblers are quite plain, with a delicately gradated edging of colour round the brim. The tall beakers, which hold a pint or more, are sometimes laced round with the thinnest possible thread of coloured glass, and then, in order to give the hand a firmer grasp, the lower end of the tumbler is enriched with bosses of the same hue. I must not omit to mention the opal glass, which transmits a rich and lovely iridescent light, exactly like the precious stone from which it is named.

Of course the smooth perfections and stereotyped neatness of ordinary English goods are neither aimed at nor found in this ware. But if fair colour, free grace of form, and artistic quality of material, constitute excellence in such manufacture, this is the best modern table glass which has been produced.

Technical enigmas in connection with colour and the new conditions of form had to be solved, and even the most experienced workmen required some little time before their heads and hands became accustomed to the novel character and the delicacy of the work before them. At first, as might have been expected, the specimens forwarded to England were somewhat crude in conception and a little clumsy in form. But as fresh consignments arrived, a marked improvement was noticeable, and by degrees the Venetian glass of the nineteenth century is approaching, in vigour of design and in the spirit of its execution, those beautiful examples which, after a lapse of nearly three centuries, still command our admiration. In this country the lovers of art-manufacture have reason to be well satisfied with this result, and, indeed, there is only one class of persons whom it is likely to displease. For many years past the examples of old Venetian glass which came to the market through public auction, or which still lingered on the shelves of old curiosity shops, have fetched a very high price; nor can we wonder at this when we remember that such fragile objects are liable to injury and breakage whenever they change hands, and that every year must diminish their number. In addition to this fact, there was, until lately, no prospect of the manufacture being revived, and that naturally enhanced their worth. But now, when almost every characteristic of the old work can be reproduced with a fidelity which surprises even the experienced connoisseur, at about a tenth part of what it used to cost in price, the commercial value of the original ware must to some extent depreciate.

It is not too much to say for this modest but interesting effort at reform in the manufacture of table glass, that it marks an important era in the history of industrial art. In no other direction that can be named - neither in the design of cabinet work, ceramic productions, or jewellery, have we moderns realised so nearly the tastes and excellences of a by-gone age; and it will be a curious coincidence if, after years of humiliation and bondage, Venice should be enabled to revive one of the sources of her ancient wealth in the same epoch which has restored her to political and national freedom.

Continue to: