Flying Fish

Description

This section is from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana. Also available from Amazon: The New American Cyclopędia. 16 volumes complete..

Flying Fish

Flying Fish (exocoetus, Linn.), a genus of fishes belonging to the order pharyngognatlii and the family scomberesocidoe (Muller), containing, according to Valenciennes, 33 species. This genus is at once recognizable by its large pectoral fins, capable of being used as parachutes, and to a certain extent as wings; other fishes have the faculty of leaping out of the water and of sustaining themselves in the air for a short time, but the exocceti far excel these, and approach much nearer in this act the true flight of birds than does the flying dragon or the flying squirrel. Navigators in all tropical seas are familiar with these sprightly fishes, which relieve the monotony of ocean life as birds do the silence of the woods. The characters of the long pectorals, the strength of the muscles which move them, and the size of the bony arch to which they are attached, are the essential conditions of their flight. Numerous observations prove that these shining bands pursue their flights when no danger threatens, in the full enjoyment of happiness and security, for mere sport, and probably as a necessity of their structure.

Their lot indeed would be far from enviable were their flights the frantic attempts to escape from pursuing bonitos and dolphins (coryphoena), for in the air their danger is quite as great from the albatross, frigate pelicans, petrels, and other ocean birds. This habit belongs to the same class of phenomena as the flying of the dragon and squirrel, the climbing of trees by the anabas, and the travelling across the land by the common eel. Humboldt drew attention to the great muscular force necessary for the flight of these fishes; he recognized that the nerves supplying the pectorals are three times as large as those going to the ventrals; the muscular power is sufficient to raise them 15 or 20 ft. above the surface, and to sustain them with a velocity greater than that of the fastest ship for a distance of several hundred feet. The pectorals strike the air with rapid impulses, scarcely more perceptible than the quick vibrations of the humming bird's wing. Humboldt says they move in a right line, in a direction opposite to that of the waves, but other observers assert positively that they can turn nearly to a right angle from this course before settling into the water again; though they generally come out on the top of a wave, they can pass over several of their summits before descending.

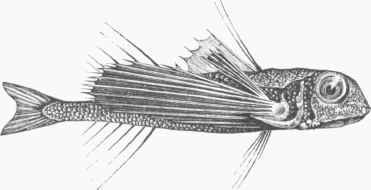

The size of the swimming bladder is enormous, occupying more than half the length of the body: though this, not com-municating with the intestine, is of no advantage in making the exit from the water, it contributes to prolong the flight by rendering the body more buoyant. The flying faculty of these fishes, the pleasing spectacle of their troops sporting around the bows of vessels, the glittering of their beautiful colors in the tropical sun, the delicate flavor of their flesh, and the fact of their frequently leaping on board ships, have attracted the attention of mariners from early times; but until a comparatively recent period only two species were admitted by naturalists, who gave them a distribution as wide as the tropical and temperate seas. The order to which the flying fish belongs is characterized by having the lower pharyngeal bones united to form a single bone. The generic characters of exocoetus are: a head and body covered with scales, with a scaly keel on each flank; the pectoral fins nearly as long as the body; the dorsal over the anal; the head flattened, with large eyes; both jaws with small pointed teeth, and the pharyngeals with numerous compressed ones; upper lobe of the tail smaller than the lower; the fins without spines; the intestine straight, without pyloric caeca.-The common flying fish of the Mediterranean {E. volitans, Linn.) is recognized by its long white ventral fins; the body is generally short and thick, robust in the pectoral region, rounded above, flattened on the sides; the head is large, the muzzle obtuse, the lower jaw the longer, the mouth small, the teeth in the anterior part of the jaw, the palate smooth, the tongue free, the gill openings large, and the branchial rays 10 to 12; the humeral bones are large and firmly articulated to the head, and the pectorals, which are attached to them, are so arranged that when the flexors contract the tins are spread horizontally, and are applied along the sides when the wings are shut; the movements do not differ from those of other fishes except in the freedom permitted by the articulation; the fin rays are very long, and not deeply divided; the ventrals, inserted in front of the middle of the body, are completely abdominal and well developed; the dorsal is small, low, and triangular; the anal very short, and the caudal deeply forked; the swimming bladder extends along the spine even under the last caudal vertebrae, protected by their lower bony arches, a disposition found in no other fish.

The general color is a leaden gray, with greenish tints on the upper half of the body, and silvery white below; the pectorals have a wide whitish border; the dorsal is gray, the caudal brown, the anal bluish, and the ventrals whitish. The largest specimens are rarely more than 16 in. long, and they are found in all parts of the Mediterranean. The E. exolans (Linn.) is found in so many parts of the world, that it may be called cosmopolitan. The average length is between 8 and 9 in.; the eyes are of moderate size, the teeth very small, the dorsal and anal fins long and low, the pectorals extending to the caudal, the ventrals very short and attached to the anterior third of the body; the color is rich ultramarine blue on the back, and silvery on the abdomen; the fins are of a darker blue, the pectorals being unspotted. There are five species on the coast of North America, which have been divided into three genera by Dr.

European Flying Fish (Exocoetus volitans).

Weinland. The common species (E. exiliens, Gmel.), found from the gulf of Mexico to the coast of New Jersey, is from 12. to 16 in. long, with dusky pectorals and ventrals, banded with brown in young specimens; the ventrals are longer than the anal, and nearer the vent; the dorsal and lower lobe of the caudal are spotted with brown and black. The New York flying fish (E. Noveboracensis, Mitch.), about a foot long, has been found from the middle states to Newfoundland; the color above is dark green, the pectorals brown with the end bordered with white; the ventrals are very long, nearest to the vent, and the wings reach to the tail.-Some species have the lower lip much developed, with one or two tough appendages hanging from the chin; these have been separated as the genus cypselnrus, and include two species of our coast. The 0. comatus (Mitch.) has a black cirrhus on the chin extending half the length of the body, which is about 5 in.; the pectorals do not extend to the end of the ventrals, the latter touching the caudal; it has been found from New York to the southern states. The C. furcatus (Mitch.) has two appendages from the lower jaw; it is 3 to 5 in. long, and extends from New York to the gulf of Mexico; the pectorals are large, and the ventrals very long.

The middling riving fish Dr. Weinland has made the type of a new genus halocypselus; this species(H. mesogaster, Weinland) is found in the West Indies, varying in length from 4 to 7 in.; the ventrals are very short, about one quarter as long as the pectorals, anterior to the middle of the body, between the anus and the pectorals; the lower jaw is angular.-The flying gurnard (dactylopterus volitams, Cuv.), a spiny fish of the family triglidae or sclerogenidw, has also been called flying fish by navigators. The species has been described as occurring in the Mediterranean, in the tropical seas, in the West Indies, and the gulf of Mexico, and along the American coast from Newfoundland southward; probably more than one species will be found over such an extended range. These flying fish or sea swallows behave very much like the exocceti, swimming in immense shoals, leaping out of the water for sport and for safety, preyed upon by marine and aerial enemies, and falling in consequence into equally cruel hands on board vessels which come within their range. From the rapid drying of their pectorals and their less muscular power, they fall into the water again sooner than do the true flying fish; their pectorals serve merely as parachutes.

They vary from 6 to 8 in. in length.

Flying Gurnard (Dactylopterus volitans).

Continue to: