The Training Of An Illustrator. A Preliminary Glance At Past And Present Mediums Of Reproduction

Description

This section is from the book "Arts & Crafts Magazine Vol1-2", by Hutchinson & Company.

The Training Of An Illustrator. A Preliminary Glance At Past And Present Mediums Of Reproduction

The held for illustration for publication is so much wider now than formerly, that it is not surprising to find it crowded with eager aspirants who, under the old conditions, would not have dreamed of entering it. The change has been brought about by the magic influence of " Process," which is the curiously unscientific designation of the mechanical means by which nowadays virtually all book, magazine, newspaper and commercial illustrations are reproduced for printing. By its agency, any drawing in black and white, made under certain technical rules easily followed, may be photographically reproduced on a relief plate of zinc or type metal, from which virtually any number of impressions may be obtained at a comparatively small expense. Thus " process " enables one who is not necessarily an illustrator by profession to draw for illustration. Formerly the artist's design had to be drawn (in reverse) upon a block of box-wood, which was then turned over to the " wood engraver," who, with more or less skill, proceeded to chop away the artist's work, line by line, and create " tints" of his own (composed of series of parallel lines), which were supposed to approximate the wash effects of the; original. Early in "the seventies," an American invented a way to obviate this truly Chinese method of destroying a drawing in order to obtain the means of reproducing it, by the simple device of photographing the artist's drawing directly upon the block (without reversing), enabling the engraver to keep the original before him as a guide. In turn, this gave way to that far greater triumph of photography, the typographic process-block, pretty much as we have it to-day. By-and-by we shall describe the principal photographic reproductive processes used for illustration, but for the present, let it suffice to say that the possibility of "process" rests on the simple fact that such substances as bitumen or gelatine, in connection with a chromic salt, are rendered insoluble by the action of light. If the metal plate is covered with a bichromated gelatine solution, and when dry is exposed to light, under a negative, the gelatine will become insoluble in those parts upon which the light has acted - that is, under the lines of the negative. By immersing such an exposed plate in warm water, all the soluble gelatine will be washed away, leaving the metal bare. Or the plate may be inked up and immersed in cold water, and the ink removed from the still soluble portions by gentle friction with a soft sponge. In this case the lines of the negative will be reproduced in blaek ink on a ground of gelatine. Such a plate with proper treatment can be etched into high relief. Owing to its simplicity, cheapness and wide range of application, photo-zincography is the most important of photo-engraving methods. Typographic blocks are of two classes: (a) line blocks, known to the trade as "zincos," and (b)

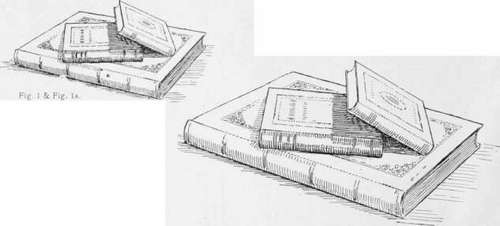

Fig. 2. - The Pen Drawing on the opposite page, reduced to half size.

Figs. 1 & 1a show the same Drawing after and before reduction. The example suggests things to avoid - for instance, a continuous outline, even in a book. Compare with Figs 2 & 2a, and with the admirable study, p. 21.

Original Size of the Drawing shown on the opposite page in reduction.

"half-tone" blocks. Zincos are used for-direct reproduction of line drawings - those in pen and ink in particular - and for line prints. The illustrations in Arts and Crafts all belong to either one or ths other of these classes, but chiefly of the first named. It is to this branch of the subject we shall at first confine our remarks, beginning next month with a series of elementary exercises for'pen practice.

(To be continued.)

First of the Series: Lilacs. Pen Drawing by Victor Dangon.

(For suggestions for treatment in oil and water colours, see page 18.)

Continue to: