On The Painting Of Children

Description

This section is from "Every Woman's Encyclopaedia". Also available from Amazon: Every Woman's Encyclopaedia.

On The Painting Of Children

In this article, which she has specially contributed to "Every Woman's Encyclopedia" Mrs. Seymour Lucas, herself a painter of renown and the wife of a great artist, gives valuable and helpful advice to those whose tastes and talents beckon them to the pursuit of art. As the writer remarks, "Art is a hard taskmistress" and she does not shrink from showing its intending votaries plain facts. But, though candid, her words are full of encouragement to those who have the necessary perseverance

Nothing is farther from my thoughts than to attempt to lay down the law for the guidance of others. I want that fact to be very clearly understood by everyone who reads this article. As a matter of fact, I have the greatest possible dislike to discuss in print the question of painting children - or, for the matter of that, the painting of anything else. My reason is the very simple one that people are so apt nowadays to misinterpret the motives which induce one to give even a reluctant consent to appearing in print at all.

It is only the consideration which has been urged very strongly upon me by the Editors of Every Woman's Encyclopedia that my experience may possibly help other women in the pursuit of their art, that has induced me to overcome the very grave objections to which I have referred, and to consent to fall in with their desires.

The embarking on a career in art is one which, in my opinion, should not be undertaken lightly. Many people, unfortunately, start in the belief that the artist's is an easy life, which gives plenty of opportunity for enjoyment, and is full of that free and easy "Bohemianism" which looks so attractive on the outside.

Let me earnestly entreat everyone to disabuse his or her mind of this fallacy. •

A Stern Truth

Art is a hard taskmistress. The words have become a proverb. They are true. I have lived all my life in the world of art, and I have known the greatest painters of my time. Yet I have seen the unceasing study these men devote to their work, for the earnest painter never ceases to be a student. Not only that, but I have seen the strain under which they live in their attempt to set down on canvas what their imagination has conceived and their eves have seen. I have watched the difficulties they have had to wrestle with, and the problems they have had to solve by dint of long hours of hard labour, and I know how far from easy is the life. I know all this, not only as an artist myself and the wife of an artist, but also by-having lived all my life among artists.

Very many people have a sincere taste for art. This begets a desire to practise art professionally, and they find out, only too late, that they have no talent for the vocation The result is they are stranded early in their art life. Perhaps that is better than being stranded later, for youth has a certain elasticity, and those who find out their mistake when they are young can turn to something else before it is too late.

Unless, therefore, a girl has a true and decided bent towards art, and unquestionable facility in her work, and has been told by someone whose opinion is worth having that she has a gift for it. it is far better for her to devote her attention to something else.

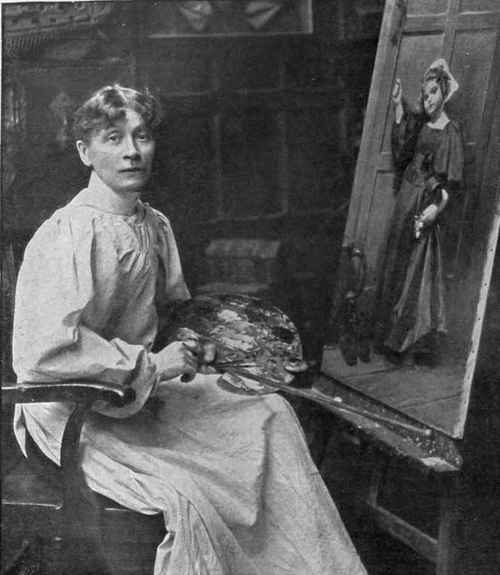

Mrs. Seymour Lucas, the distinguished wife of a distinguished husband. Mr. and Mrs. Lucas are one of the rare instances of a gifted husband and wife following the same calling. Their artistic excellences are, however, in different fields of art

Photo, E. H. Mills

I suppose the same thing might be said with equal justice as regards any other calling. As an artist, however, the question appeals to me in the strongest light in relation to my own profession.

Presupposing the possession of the qualities to which I have referred, the question of education must naturally then receive consideration. I was a very little girl myself when I first began to develop a taste for art. My mother was a friend of that great artist, Rosa Bonheur, and was herself also an amateur artist of some merit. She was my first teacher, and she and my father gave me every encouragement, although I owe much also to my master, Mr. John Parker.

I succeeded in passing from one of the Kensington Art Schools into the Royal Academy School. It was the time when students took months to make a finished drawing from the antique, the stippling being done with what might be, and is now, regarded as unnecessary care, though personally I believe enormously in this method of training for the young student. I should like to see much more attention given to it than is done at present.

I am convinced that it is impossible to improve on the old methods. To-day, however, is not the age of art. It is the age of science.

The greatest age of art of which we know anything at present is that of the Greeks. In it there was no so-called "impressionism" or "post impressionism " to disguise the lack of ability on the part of the artist. Eccentricity is not art.

It is as an artist that I feel strongly on the question of the true as against the false.

Let me, therefore, entreat the young artist not to go wandering in the wilderness after these new and constantly changing fashions, but to keep to the simple, sane paths of art in which the best artists have walked.

The Appeal Of Childhood

In the Academy Schools I remained for three years. Then I married, and continued my studies at home.

I have always liked painting children. I do not think that, apart from the work of the schools, I have ever painted anything else. My own children, being pretty and very "paintable," were my principal models. Childhood has always appealed to me as an artist. People constantly ask me whether, as I paint children so much, I am not a great lover of them. I suppose every healthy minded woman does love little children. Their helplessness when they are little, the infinite possibilities in their natures, even their ways of looking at things, all strike distinctive notes in our hearts. Yet I cannot confess to being a lover of children in the way that some women are. 1 cannot, for instance, pick up every dirty and untidy little child in the street and kiss and fondle it. Some women can do that.

Continue to: