Part 171. Plant Evolution In General - Kinship And Adaptation

Description

This section is from the book "Plants And Their Uses - An Introduction To Botany", by Frederick Leroy Sargent. Also available from Amazon: Plants And Their Uses; An Introduction To Botany.

Part 171. Plant Evolution In General - Kinship And Adaptation

Part 171. Evolution in general. The creation of living things by successive steps, one growing out of another, is viewed by modern science as part of a gradual process of world-making which is understood to proceed in a somewhat similar manner. That is to say, the entire universe is believed to have evolved and to be evolving according to laws of change which have been the same from the beginning and will be the same to the end, or forever, if the process be endless.

The view most widely accepted is that from a vast nebula or vapor-like mass of incandescent star-dust, like those now seen in various parts of the heavens, our solar system for example with its central sun, its whirling planets and their moons, has slowly developed during countless ages, through the agency of gravitation acting together with other properties of matter. During the course of its evolution each sphere is supposed to pass from a nebulous condition to a ball of glowing liquid, which, as it cools forms at first a solid crust, and finally becomes cold and firm to the core. This view of world evolution is called the nebular hypothesis.1

1 A rival view known as the planetesimal hypothesis has of late years been gaining ground among geologists. This differs from the nebular hypothesis in supposing that such a solar system as our own evolves by the slow aggregation of innumerable small cold solid bodies (planetesimals) moving through space in rings or orbits like those of our planets. They are consequently drawn together without much violence into larger and larger masses by mutual attraction until there is formed a central sun and planets none of which at any time are altogether gaseous or liquid. Once these larger spheres are formed, other forces than those of mere shrinking with loss of heat are assumed to account for such geologic changes as those of which we have evidence.

According to the nebular hypothesis, as the molten interior of our earth lost heat it shrunk away from the solid crust, which, following it warped and wrinkled in an uneven way somewhat as the skin of a drying apple wrinkles to fit the shrinking pulp. When the earth was cool enough at the surface to permit condensation of the atmospheric watery vapor and its fall as rain, seas began to form in depressions between the upheaved regions of dry land. Subterranean forces, connected with the further loss of heat, continued to wrinkle the land into chains of mountains. Meanwhile storms, controlled by heat from the sun, brought water to the highlands from the sea to which it returned in streams cutting through the land and carving the surface into varied shapes. The rock waste carried seaward settled off shore, as layers of gravel, sand, or mud. These deposits in time became compacted into solid rock and were slowly upheaved again above the level of the sea. This new land was again washed into the sea or may have sunk beneath it and been covered by newer washings which later may have been again upraised. From such working over of the crust, most of the land, with its many layers of rock or soil (which is rock waste on its seaward way) came to be as it is. From the many changes thus wrought-some gradual, some sudden-involving wide sway of air and water currents, and the continual though slow redistribution of rock materials-from all this has resulted a greater and greater variety of climate and soil- in a word, a progressive differentiation of the conditions affecting life. This differentiation represents more and more varied sets of conditions offering fresh opportunities for living things.

Life as we know it is possible only below a certain temperature. The greatest heat in which living things are found to grow is that of certain hot springs where, it is reported that a centigrade thermometer registers about 55° (equivalent to 131° Fahrenheit). It will be remembered that water scalds at about 60° C. or 140° F. Under these extraordinary conditions, certain microscopic plants of most simple organizations are found to thrive.1 It is fair to assume therefore that living creatures could not have appeared upon the earth until the crust had so far cooled that the waters were considerably below their boiling-point. Since the simplest forms of life we know and the oldest fossils we have, are aquatic, it is probable that the first living things appeared in the water; and since all the animals we know depend directly or indirectly upon vegetable food, it seems most likely that the earliest organisms were plants and that from them animals evolved.

1 Experiment shows that the spores of other very simple plants are not killed by a temperature considerably above that of boiling water, but they cannot grow under such conditions.

Confining our view to the vegetable kingdom, which here chiefly concerns us, we may picture to ourselves its evolution as proceeding in a general way from plants of comparatively simple organization, to those whose structure is more and more complex, greater morphological differentiation accompanying fuller physiological division of labor. Such increase in complexity we speak of as progress from lower to higher organization, without meaning to imply that the higher forms are any more perfectly adapted than the lower to their respective environments. Indeed the simpler forms may be so well adapted to the less trying conditions that they may persist through countless generations essentially unchanged, provided thay have the opportunity to live in the kind of environment which suits them. Thus we find to-day, growing in water, plants which may be fairly supposed to have retained the main features characteristic of the progenitors of the vegetable kingdom.

Many types of structure have become extinct, because changing conditions no longer afforded a suitable environment, or, perhaps because no mutations of the old form could adapt it to new circumstances of peculiar difficulty. Relics of types which the world has thus outgrown have occasionally come down to us as fossils caught in the deposits which became rock in ages past.

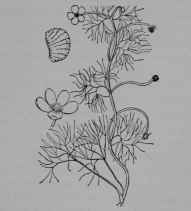

Sometimes a group, or perhaps part of its members, may have escaped extinction through the appearance of mutations fitting the individuals to live under less exacting conditions which therefore would permit simpler structure. Thus a buttercup able to live in water without being drowned could dispense with much of its root system and stiffening framework and so come to resemble, in the adaptation of its vegetative organs to an aquatic life, a lower form of plant none of whose ancestors had been terrestrial. The white water crowfoot (Fig. 304) of our ponds and streams is a buttercup which we have every reason to believe has thus descended from a land species. In so far as a type of organism or organ becomes simplified in the course of its evolution and, so passes to a lower level of structure, it is said to degenerate. Much more extreme instances of degeneration will be dealt with in the following chapter.

Fig. 304.-White Water Crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis, var. capillaceus, Crowfoot Family, Ranunculaceoe). Plant, about 1/3. Flower. Fruit. (Britton and Brown.)-Perennial (?) herb about 30 cm. long; leaves submerged; flowers white; fruit dry. Native home, North America and Eurasia.

It thus appears that degeneration, persistence, and extinction of types accompanies the general progress which characterizes organic evolution. In the evolution of human society likewise we find degeneration, persistence, and extinction of races along with a general progress of mankind from savagery to civilization. Here as in the evolution of lower organisms we may observe adaptation to changed conditions through sudden or gradual modification. Migrations also play an important part and have many consequences, among which conflicts are the most apparent although not necessarily the most significant. Periods of greater progress have been times of greater peace. Conflicts destroy or test; they do not create. Men or races unfit to live, if such there be, of course are better dead, and those menacing the progress of mankind are better subdued; but it is surely a partial view of human affairs that regards the world as one vast battlefield whose horrors have fostered the most precious characteristics of civilization. However inevitable mortal conflicts have been, however fierce the struggle of competition, and however necessary it may have been to kill the worse that the better might live, we cannot say that anyone has been made better by the killing. Yet we may be sure that human advance toward the most perfect and abundant life has been delayed, and that whatever real progress Man has made has been in spite of his competitive struggles. The economies of co-operation and the advantages of mutual service achieve what competition never can. Mere struggle for supremacy when fiercest destroys most of what is best. Man's mastery over nature and over his lower self has come through learning and choosing the better way.

The evolution of mankind and that of lower organisms are alike in so many ways, it is thought that each may throw light upon the other. In human progress we recognize as the controlling factors of change: Opportunity,-offered by the environment; Experience,-representing its effect; Choice,- as the response to it, guided by Ideals. Of these the pivotal factor is Choice, for by it opportunities are improved, experience determined, and ideals pursued. What we ourselves and what former generations have chosen to do or endure is most largely responsible for what we are. Thus human affairs center about the human will. So throughout God's world we are led to look for some opportunity offered to every creature, some experience by which it may profit, some choice of its own, and some divine guidance.

Man's choosing of the better way has led him heavenwards toward the highest, fullest life. As from a mountain side he may now look back and with the mind's eye catch glimpses of his path and of the forking paths of fellow creatures many of whom have been as comrades at different stages of the long, long journey. Traced backward all the paths seem to converge at the horizon as if all had come from the same point. Some of them, as they advance, keep to the level of the sea continuing always much the same; others climb for awhile to higher levels, then turning aside and traversing an easy plateau end at a precipice; still others after climbing for a while decline to lower levels; while others yet keep climbing and attaining various heights. Man's path soon left the kingdom of plants, and ascending through the realms of worm, fish, reptile, and brute has reached at last the mountain path which leads beyond the clouds.

Viewed broadly the progress of the world is seen to be orderly, and shall we not say, well ordered? New forms of life have come promptly to enjoy the ever increasing opportunities afforded by the evolving earth. Advance has been made not without difficulties, which being overcome have brought out the finest traits. Nor has there been lacking continual occasion for mutual help, and this has ever multiplied the blessings of life.

Continue to: