Embolism. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "A Manual Of Pathology", by Joseph Coats, Lewis K. Sutherland. Also available from Amazon: A Manual Of Pathology.

Embolism. Part 2

The phenomena of embolism in the case of end arteries may be included in three processes which manifest themselves separately or in combination, according to the circumstances of the case; these are (1) Engorgement, (2) Haemorrhage, and (3) Necrosis.

(1) Engorgement

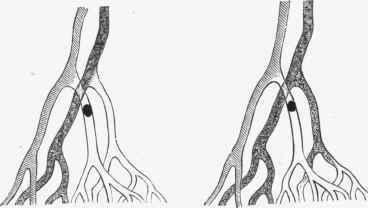

Engorgement is a great distension of the veins and capillaries with blood; in fact, an extreme passive hyperemia. The mode in which this results from the obstruction of an artery has been well elucidated bv the observations of Cohnheim and others. Cohnheim observed the process in the tongue of the frog, where he produced embolism by the introduction of blackened pellets of wax by the aorta. The immediate effect of obstruction of an end artery was usually ischsemia in all the vessels of the part. (See Fig. 31.) Soon, however, a backward flow of blood from the veins was observed, and this produced an engorgement of all the vessels, capillaries, veins, and even the branches of the artery. The explanation of this phenomenon obviously is that, the blood being suddenly deprived of the vis a tergo by the obstruction of the artery, the blood-pressure in all the vessels is reduced to nil. But the vessels are still in communication with the veins and capillaries around, and so the blood, passing in the direction of least resistance, passes backwards from the veins into the vessels of the part.

(2) Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage was, in Cohnheim's observations, seen to follow on the engorgement, and it took place by diapedesis. It is simply an exaggerated form of the haemorrhage which we have seen to occur in passive hyperaemia, but in this case the nutritive defect in the vessel-walls is a more potent agent.

The haemorrhagic infarction, which is most typically seen in the lungs, is the result of the conjunction of the two processes of engorgement and haemorrhage. Microscopically examined, the blood-vessels are distended with blood, and the lung alveoli are filled with blood to the exclusion of the air. The condition results from embolism of the pulmonary artery, and the piece of tissue involved is wedge-shaped. This piece of tissue is solidified, and presents a deep red colour, as if a solid blood-clot had replaced the lung tissue. (See under Lung).

Fig. 81. - Diagram of conditions following embolism of an end artery. In the figure to the left the state of ischiemia immediately after the embolism is shown. In the other figure the regurgitant current from the vein is indicated. (After Cohnheim).

Engorgement of the vessels is ascribed by Cohnheim to the regurgitant current from the veins, but further observation has shown that when an artery is obstructed blood flows into the capillaries from all surrounding communications, from arteries and capillaries as well as veins, and the engorgement may be due to the flow from these as much as from the veins. Moreover, the.current from the communicating arteries and capillaries may be sufficiently strong to carry on the circulation and prevent any considerable engorgement or diapedesis. This is. frequently the case in the lungs, where the htemorrhagie infarction often fails to develop after embolism. The circulation in the lungs is somewhat special. The capillaries are wide and very abundant, and the bronchial artery not only supplies nutrient branches to the lung tissue but forms anastomosing communications with the pulmonary artery. In consequence there may be none of the phenomena of the haemorrhagic infarction, and even if the engorgement and haemorrhage occur, the process usually stops short of an actual necrosis of the tissue. It has been asserted by Grawitz, Hamilton, and others that the hasmorrhagic infarction of the lung is not produced in the way described above, and is not truly embolic in character. The author has, from repeated observations, convinced himself of the embolic character of the condition, and concurs with the view of Cohnheim, recently supported by the further experiments of Orth and Fujinami.

(3) Necrosis Or Death Of The Tissue

Necrosis Or Death Of The Tissue sometimes follows o,n the haemorrhagic infarction, but it may not so result, and, on the other hand, we often have necrosis without engorgement or haemorrhage. In order to engorgement the vessels must remain alive, otherwise the blood will coagulate and obstruct any backward current. But necrosis may occur before time has been given for engorgement, or the engorgement may be limited to the peripheral parts. In the spleen and kidneys this is frequently the case. The tissue, especially if the artery be of large size, dies without any considerable engorgement, and in these organs the dead tissue undergoes a peculiar process of coagulation (see Coagulation Necrosis), the result being the formation of a dense pale wedge, the white infarction. In the spleen and kidney we have all gradations between the white and the haemorrhagic infarctions, and a white infarction is often surrounded by a red zone in which haemorrhage has occurred. In the brain and retina necrosis occurs in the form not of coagulation but of softening, and there is usually little haemorrhage, hence a white softening.

The superior mesenteric artery, although it has many anastomosing branches, is so large in comparison with these vessels that its obstruction may lead to engorgement and necrosis in the portion of intestine to which it is distributed.

The portal vein is in its distribution an end artery, but infarction does not occur as a result of plugging. The explanation is that, not only is the liver supplied by the hepatic artery in addition to the portal vein, but the blood of the former, after passing through its own proper capillaries in the walls of the vessels and connective tissue of the liver, is carried into the interlobular veins which are the terminals of the portal vein. Obstruction of the latter will not therefore stop the circulation.

It will be obvious that arteries possessing free anastomoses may be reduced to the condition of end arteries if their anastomoses are no longer available. If, as sometimes happens, an embolus passing to the leg breaks up, say, by being propelled against a bifurcation, and is scattered to a number of stems simultaneously, then the circulation will be reestablished very slowly or not at all, and necrosis is liable to occur, especially if the circulation is already feeble. Thus, we may have gangrene of the toes occurring in this way. It is to be added that, in old people, obstruction of a number of arteries sometimes occurs from thrombosis as a result of atheroma, and this may likewise lead to necrosis.

Continue to: