Gastric Ulcer Vs. Gastric Cancer

Description

This section is from the book "Early Detection And Diagnosis Of Cancer", by Walter E. O'Donnell. Also available from Amazon: Early Detection And Diagnosis Of Cancer.

Gastric Ulcer Vs. Gastric Cancer

It will be noted that the clinical and morphologic picture of a gastric ulcer may often be presented by gastric cancer. Controversy has raged for over fifty years as to whether carcinoma of the stomach can arise from a gastric ulcer. That is, can a previously benign gastric ulcer undergo "malignant degeneration" and become cancer? If so, how often does this happen?

Many extreme views have been expressed, but a conservative majority opinion might be summarized as follows:

1. Most stomach cancer does not arise from a pre-existing benign ulcer.

2. Carcinoma may ulcerate, however, and produce the clinical and morphologic picture of ulcer.

3. Room must be left for the hypothesis that a small percentage of carcinomas (possibly 5%) may arise from benign ulcer. This, however, should not be interpreted as meaning that 5% of all benign gastric ulcers will become malignant.

4. It is often difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish benign from malignant ulcerations clinically. The problem is not so much whether the particular ulcer that is perplexing the clinician may become cancer as whether it is cancer.

Location

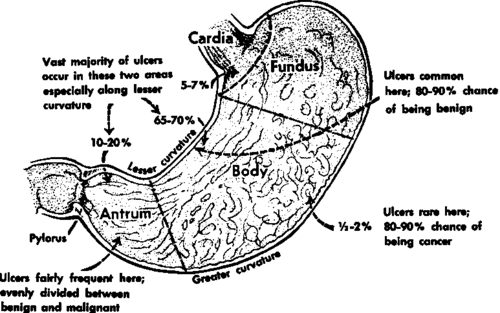

Carcinoma of the stomach has a predilection for certain sites of origin within the organ. These are best represented diagrammatically as shown in Fig. 60.

Fig. 60. Location of gastric cancer.

There is no clear-cut relationship between the type of stomach cancer and its site of origin.

The location of the lesion, as well as its type, size, and growth rate, quite naturally plays an important role in the symptoms, signs, and other clinical features of the individual case.

Premalignant Conditions

A number of conditions have been described that carry with them an increased risk of stomach cancer. The only apparent common denominator shared by these lesions is that of diminished or absent stomach acidity. It is likely that this and the underlying mucosal atrophy which often accompanies it is the crucial factor in heightening the risk of stomach cancer. Nevertheless, the various en-tides will be considered separately since this is the traditional approach.

Diminished Or Absent Gastric Acid

Evidence linking the state of gastric acidity with the risk of cancer development appears to be incontrovertible. It is derived from the following information:

1. Over 90% of patients with stomach cancer will show markedly diminished or absent acidity at the time of diagnosis.

2. The subsequent incidence of stomach cancer in individuals known to have diminished or absent gastric acidity prior to any diagnosis has been estimated as up to ten times greater than that of those with normal acidity.

3. In virtually 100% of the cases of other recognized premalignant states (gastric polyps, pernicious anemia, etc.), there is diminished or absent acid.

It is true that the frequency of hypoacidity or anacidity increases with advancing years, but its incidence seldom exceeds 15 to 30% of persons past the age of 50 years. However, this information should serve to earmark such individuals as being at higher risk of developing stomach cancer at some time during their remaining years of life.

Gastric Polyps

Adenomatous polyps of the stomach have been indicted as premalignant lesions on the basis of the following evidence:

1. Polyps are a fairly frequent finding in stomachs which also contain cancer.

2. The morphology of certain well-established cancers is such as to suggest origin in a benign polyp. Whether clinically and pathologically benign lesions would culminate in frank cancer if left unattended is a debatable point. Some authorities insist they are malignant from their inception or not at all; i.e. there is no malignant degeneration.

3. At the time of surgical removal, 10 to 30% of gastric polyps will have microscopic evidence of cancer. The percentage becomes higher if the lesions are larger than 2 cm. in diameter and are multiple. Just what the invasive potential of these malignant polyps is remains a question. Most gastric polyps are several centimeters in size when diagnosed.

4. Polyps occur in association with pernicious anemia and diminished or absent acidity. Both of these conditions carry an increased risk of subsequent cancer development.

Pernicious Anemia

It has been found that pernicious anemia, with its attendant gastric mucosal atrophy and anacidity, carries a sharply increased risk of subsequent stomach cancer. An idea of the magnitude may be gained from the following:

1. Approximately 10% of patients with pernicious anemia die of stomach cancer.

2. The risk is estimated as anywhere up to ten times above average.

This association has become appreciated more in recent years with the increasing life span of patients with pernicious anemia. It should be emphasized that even the best of treatment for the anemia has no influence on the risk of subsequent cancer development; the underlying gastric mucosal alteration and anacidity remain unchanged.

The stomach cancer which occurs in patients with pernicious anemia may show certain common characteristics:

1. Polypoid or fungating type

2. Location in the fundus or cardia

3. Multiple sites of origin

4. Tendency toward low-grade malignancy

5. Often asymptomatic until late because of location

Gastric Ulcer

Ulcerating lesions of the stomach fall into one of three categories:

1. A significant percentage, possibly 10 to 20%, will actually be cancer when first seen.

2. A lesser percentage are benign when first seen but will become cancer over an indeterminate number of months or even years. Possibly 5% of gastric cancer arises in this fashion, although estimates vary widely and some would deny this altogether.

3. Comprising by far the largest group of all are those gastric ulcers which are benign when first seen and will always remain so.

The unfortunate fact is that there is no absolute or foolproof clinical method of deciding to which of these cctegories a given gastric ulcer belongs. Thus from a practical standpoint all ulcerating lesions of the stomach must he regarded as possibly malignant.

It is in this highly qualified sense that a gastric ulcer has been included under the heading of premalignant lesions.

Fig. 61. Location of gastric ulcers.

Location

The usual location of gastric ulcers is shown in Fig. 61. The significance of the various locations with respect to the chances of a particular lesion being benign or malignant is also noted.

Attention will be directed toward the differential diagnosis of benign vs. malignant ulceration of the stomach later in this chapter (p. 196 ff.).

Continue to: