Laying Out The Work

Description

This section is from the book "Woodworking For Beginners: A Manual for Amateurs", by Charles G. Wheeler. Also available from Amazon: Woodworking For Beginners.

Laying Out The Work

Try to get the measurements and lines exact, and do not be satisfied with coming within an eighth of an inch. You cannot do good work unless it is laid out right, and cutting exactly to a line will do no good if the line is in the wrong place. It makes no difference how accurately you saw off a board if you have marked it half an inch too short, nor how nicely you make the two parts of a joint if you have laid them out so that they can not fit together. The work is spoiled in either case.

Go over all your measurements a second time. It is a good plan to check them by measuring back in the opposite direction, just as you prove your addition of a column of figures downward by adding again upward. Nothing is easier than to make mistakes in measuring. No amount of experience will prevent the chance of it. It takes but little time to measure twice, much less time than to correct mistakes - as you will discover when you cut off a mahogany board five inches too short and have to go half a mile to the mill and pay a dollar or two for a new piece.

In getting out stock for nice work it is best to make plenty of allowance for the pranks which expansion and contraction may play with the pieces (see Appendix). How to arrange the various parts of your work with regard to this swelling and shrinking, warping and winding, is a matter of practical importance, for a piece of wood can no more keep still than an active boy can, and, although its movements do not cause so widespread havoc as the motions of some boys, you will have to keep a careful eye on its actions if you wish to turn out good work.

This applies not merely to the way green wood shrinks, as we have already seen, but particularly to the way seasoned wood acts. Many people think it is only green wood that causes trouble with wood-work, but there is much difficulty with dry wood - that is, what we call dry wood. It never is really absolutely dry, except when it is baked, and kept baked (see Appendix). The moment you take it out of the kiln or oven, it begins to take up some of the moisture from the air, as we have seen, and swells. If the air becomes more damp, the wood sucks in more moisture and swells more. If the air becomes dryer, it sucks some moisture from the wood, and the wood becomes dryer and shrinks. It is thus continually swelling and shrinking, except in situations where the amount of moisture in the air does not change, or when the wood is completely waterlogged.

"What does such a little thing as that swelling and shrinking amount to? Use more nails or screws or glue and hold it so tight it cannot move." Well, it amounts to a good deal sometimes when you cannot open the drawer where your ball is, or a door or a window, without breaking something.

In the days of high-backed church pews with tall doors to every pew, each pew door would swell in damp weather, of course, and in continued dampness the doors of a certain church fitted quite snugly. There was usually no special trouble, however, for, many of the doors being open, the pew frames would give way a little so that the closed doors would open with a slight pull; but if all the doors were shut the whole line would be so tightly pressed together that it would take the utmost strength of a man to start a door. Some boys one day catching on to this idea (though they were not studying wood-work), got into the church one Sunday morning before service and by using their combined strength succeeded in closing every door. They then climbed over the top into their own pew, where they awaited developments, as one after another sedate churchgoer, after a protracted struggle, finally burst open his pew door with a ripping squeak or a bang. You will understand that those boys always remembered the expanding power of wood. I feel sure that I am not putting any boys up to improper mischief in telling this story, because pews are not so often made in that way now, and there is slight danger of their having any chance to try it.

Did you ever see stone-workers split big rocks by drilling a row of holes and driving dry wedges into them and then wetting the wedges, when the stone will split?1 Do you think nails or screws or glue will stop a force which will do that ? You cannot prevent the swelling and the shrinking any more than you can repress a boy's animal spirits. You may be able to crush the wood, but so long as it remains a sound, natural board it must swell and shrink.

What shall you do then ? Why just the same as with the boy; give it a reasonable amount of play, and a proper amount of guidance, and there will be no trouble. You must put your work together so as to allow for the expansion and contraction which you cannot prevent. You will find abundant examples, in almost every house, of work which has split or come apart or warped because proper allowance was not made for this swelling and shrinking. So try to avoid these errors so common even among workmen who should know better.

1 The peculiarity of the wood is that the water is not simply drawn in to fill up what we call the pores, as in chalk or any ordinary porous inorganic substance, but enters into the very fibre of the body, forcing apart the minute solid particles with an extraordinary force which does not seem to be fully understood.

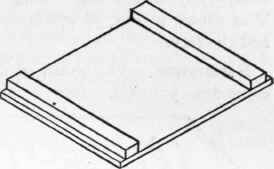

For instance, if you were to put cleats on one side of a drawing-board three feet wide, and were to firmly glue the cleats for their whole length (Fig. 35),- you sometimes see such things done, - you would probably not have to wait many weeks before you would hear a report like a toy pistol, and the cleats would be loosened for at least part of their length, because of the expansion or contraction of the board. Similar cases are continually occurring. In such cases the cleats should be screwed, the screws having play enough in their holes to allow for the changes in the board (see Appendix).

You must also make plenty of allowance for planing down edges and surfaces and for the wood wasted by sawing. No rule can be set for these allowances. If you do not leave enough spare wood, the pieces will finally come out too small. If you leave too much you will increase the amount of planing or shaping to be done, but of the two extremes it is better to err on the side of allowing too much.

A rod (any straight stick), say six feet long, and another ten or twelve feet long, with feet and inches marked, are very handy to have when laying out work roughly, or for measuring outdoor work approximately.

Lay out your work from only one edge or one surface of a piece of lumber unless you are sure the edges or surfaces are exactly parallel. Having selected the best edge for a "working edge" and the best surface for the "face," mark them with an X or other mark to avoid mistakes (Fig. 36). This is quite important in laying out a number of pieces, as before the stock is accurately worked into shape you cannot usually rely on the edges being parallel. One mark like a V as shown in Fig. 36 will indicate both the working edge and the face.

Fig. 35.

Continue to: