Rectilinear Saws Used By Hand. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "Turning And Mechanical Manipulation", by Charles Holtzapffel. Also available from Amazon: Turning and Mechanical Manipulation.

Rectilinear Saws Used By Hand. Part 3

The timber is now turned over, or with c to d, fig. 678, uppermost and the end line exactly perpendicular as before. Should the piece be very crooked or high-backed, the sawyer may be unable to see over it, and observe the central marks at the ends of the timber; such being the case, the points e,f, g, are transferred to e', f, g', on the top of the timber, by the mode explained by the figure 679, supposed to be a section through the plane e e'. A dog is driven into the timber near e', and from the dog a plumb-line, x' x, is suspended; the distance e x, is then measured with a common rule, and measured backwards from x' to e', by which process e' becomes exactly perpendicular to e; the points f and g are similarly treated to obtain the points f' g'; after which the central line is made at four operations, through c, e', f', g', d; the plank lines are set out with the compasses as before explained.

Large timber is usually cut into plank as in fig. 679; the planks are sometimes flatted or their irregular edges are sawn off and for the most part wasted; but this is not generally done until the wood is seasoned and brought into use.

When many planks are wanted of the same width, it is a more economical mode, first to leave a central parallel balk, as in fig. 680, by removing one or two boards from each side, and then to flat the balk, or reduce it into planks. The central line is in this case transferred from the lower to the upper side, by aid of the square and rule, instead of by the plumb-line.

According to Hassenfratz, the setting out shown in fig. 681 is employed in large wainscot oak, in order to obtain the greatest display of the medullary rays which constitute the principal figure in this wood; and the same author strongly advocates the method proposed by Moreau, and represented in fig. 682, in which he says one-sixth more timber is obtained than by any other mode, and also that the pieces are less liable to split and warp; but on examination there does not appear to be any inducement to incur the increased trouble in marking and sawing the timber on this method.*

When the timber has been properly marked out, the sawyers take their respective places, upon the timber and in the pit: the saw is sloped a little from the perpendicular; that is, supposing the piece about eighteen inches through or deep, the saw when it touches the top angle, is held off about two inches from the bottom. A few short trips arc then very carefully made, as much depends on the saw entering well; and should it fail to hit the line, the blade is doped to the right or left at about the angle of 45 degrees, to run the cut sideways and correct the incision in its earliest stage. It is usual to take all the cuts as in figs. 679 and 680, to the depth of three or four feet, and then the whole of them a further distance, and so on.

When the saw has penetrated three or four feet, a wooden heading wedge is driven into the cut, to separate the timber, for the relief of the saw; and when, from the length of the cut, the timber is sufficiently yielding, the hanging wedge is used, which is a stick of timber about twelve to twenty inches long and an inch square, with a projection to prevent the wedge from falling through. The wedges lessen the friction upon the saw; but if too greedily applied they split the wood, and tear up the loose parts sometimes observed in planks.

In sawing straight boards, it is advantageous that the saw should be moderately wide, as it the better serves to direct the rectilinear path of the instrument; but for curvilinear works, as the felloes of carriage wheels, the sawyer employs a much narrower saw, to enable him to follow the curve. The blade of one kind of felloe-saw is about five feet long, and it tapers from nearly four inches at the wide, to two inches at the narrow end; it is used with a tiller and box, exactly the same as the ordinary long saw, and also without a frame.

The more general felloe-saw, or pit-turning saw, has a blade about 1 1/4 inch 1 1/4 inch wide, and is stretched in a frame exactly like those represented in figs. 676 and 677. The turning-saw with two side-rails the best where it can be applied; sometimes the RIP, HAND, PANEL SAWS, frame is obliged to be made single, and with a wire and screw nuts, by which the saw is strained as in fig. 677, page 703.

• Traite de l'Art du Charpentier, par J. H. Hauenfratc. 4to. Paris, 1804. Plate12.

In cutting-out very small sweeps, as in the small wheels or trucks for wooden gun-carriages, no frame whatever can be used, and slender blades about five or six feet long, five-eighths of an inch wide, with a handle at each end, were employed for this purpose during the late war. In using the various pit-turning saws, the thick plank having been sawn out in the ordinary manner, the work is marked off on one side from a pattern or templet, and then held down, upon the head-sill of the saw-pit and one transom, by means of the holdfast before noticed.

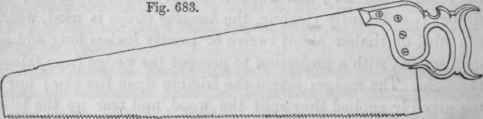

The rip-saw, half-rip, hand-saw, broken space, panel-saw, and fine-panel, which, in respect to appearance, are almost alike, may be considered to be represented by fig. 683; their differences of size will be gathered from the dimensions in the table; the chest-saws are merely diminutives of the above, and such as are used for small chests of tools, whence their name.

This kind of saw is made taper, in order that the blade may possess a nearly equal degree of stiffness throughout, notwithstanding that it is held at the one end, and receives at that end, as a thrust, the whole of the power applied to the instrument; the greater width also facilitates the attachment of the handle. Were the blade as wide at the point, as at the handle or heel, it would add useless weight, and instead of being a source of strength, it would in reality enfeeble the saw, which from the increased weight at the far end, would be more flexible near the handle than at the point.

Continue to: