The Middle Ages. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "Dutch And Flemish Furniture", by Esther Singleton. Also available from Amazon: Dutch and Flemish Furniture.

The Middle Ages. Part 2

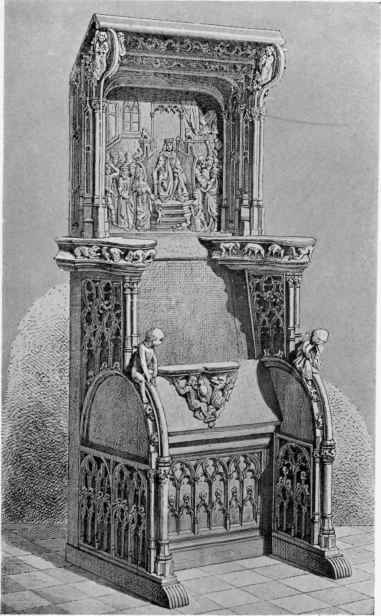

A fine example of a Mediaeval carved oak stall is shown in Plate I. By the richness of the carving it must originally have held an important position in some choir. Richly ornamented with Gothic shafting and tracery, it is a splendid example of architectural furniture. The misericorde represents a knight fighting with a dragon. The scene depicted with the chisel on the back is the favourite Judgment of Solomon. Around the elbows are various animals and men on all fours. The side scrolls under the dais are decorated with angels playing trumpets.

Plate I. - Choir-Stall.

The names of the carvers who embellished the Mediaeval choirs have, as a rule, been lost; and fire and icono-clasm have destroyed most of their work. Some few relics, however, of the splendour of wood-carving as it existed before the Renaissance are still to be found. For elaborate oak carving of the fifteenth century, it would be hard to find a more interesting example than the carved oak stalls in the great church of Bolsward (Broe-derkerk) in Holland. This was built in 1280 A.D.; but the richly carved late Gothic choir stalls date from about 1450.

One of the earliest churches of the Low Countries is that of Nivelles. The convent was founded about 650 a.d. by Ita, wife of Pepin of Landen. The Romanesque church, built in the eleventh century, somewhat spoilt by bad restoration, still stands. On the high altar is the shrine of St. Gertrude, which was carved in 1272 by the orfevres Nicolas Colars, of Douai and Jackenon of Nivelles. This work of art is famous for the delicacy and beauty of its details.

The Protestant Church of Breda (Hervormde Kerk), built in 1290, also contains notable carving, especially on the side entrances of the stalls (jouees). The choir was consecrated in 1410, and here the carvers gave free rein to satire on the clergy, representing the monks in various comical attitudes.

Examples of ecclesiastical furniture of Mediaeval days are naturally scarce, as might be expected on the "Battlefield of Europe." It is indeed astonishing that so much has survived after the ordeal by fire and sword to which the Netherlands have been so often subjected. Occasionally we come across a muniment chest. An interesting one, the front of which is perforated with quatrefoils, is to be seen in Notre Dame, Huy. This dates from 1225. Two others in the same treasury are by the hand of Godefroid de Claire, called "the noble high goldsmith"; these, however, have lost their original character, having been restored in 1560 by Jaspar, a Namur goldsmith.

The ordinary movable furniture of a castle or Mediaeval mansion was of a very primitive character. It must be remembered that in those days merchants travelled from town to town in veritable caravans. Nobles whose business or pleasure induced them constantly to be changing their residence, also travelled with an escort and baggage-train that resembled a small army. The necessary furniture and goods for the comfort of the household were carried in carts and on the backs of mules. The wooden furniture was, therefore, primitive. The tables consisted of boards and trestles; the beds were of similarly elemental construction; and what seats were taken along were also of the folding variety. The beds and benches were supplied with cushions carried in chests, and the walls were hung with printed linen or tapestry, while the floors were covered with rugs, or, in the majority of cases, with odoriferous plants, rushes, or straw. Luxury chiefly declared itself in rich products of the goldsmith's art, which were displayed on buffets of shelves rising like steps.

These customs prevailed for several centuries.

Pieces of furniture of earlier date than 1400 are exceedingly rare; and those existing had a religious destination, and are preserved in, or taken from, churches and convents.

In the fourteenth century, as Gothic Art blossomed after the disturbing influence of the Crusades, carving entered more extensively into the decoration of furniture, as it was more highly developed in ecclesiastical art. The cabinetmakers of the period were skilful carvers: in France and Flanders these huchiers-menuisiers were called upon to supply royal and princely castles with artistic furniture, the accounts of which have come down to us. We find not only carved oak, but also tables inlaid with ebony and ivory. The chief feature, however, of interior decoration during the fourteenth century was the hangings. The Genoese and Venetians still had a monopoly of the trade with the Levant; and Europe was supplied by the Italians with Oriental rugs, tablecloths and hangings. The Flemish looms also produced rich stuffs for upholstery and chamber hangings, which were often sumptuously embroidered.

Through the fourteenth century, wood-carving kept pace with the lovely stone sculpture of the cathedrals. We learn there was no light furniture in palace or castle, but that even in the lady's chamber there were only benches, trestles, forms, faldstools and armchairs. The wood-carver carved these with a mass of bas-reliefs and bosses; the carpenters surrounded them with panelling; and the artists painted them red and decorated them with white rosettes.

In studying the arts and crafts of the Middle Ages, we must always bear in mind the fact that art was not specialized. The workmen were thoroughly trained, and their artistic talents had free play. We find many men who were at once architects, sculptors, painters, goldsmiths and image-makers. This condition existed till the middle of the seventeenth century.

In the Middle Ages, the carpenter made the household furniture which formed an integral part of the dwelling; and he was quite capable of giving to it the Gothic ornamentation in vogue.

It was not till the fourteenth century that the increase of luxury and the progress of the arts demanded a division of labour; and that the huchiers and joiners formed separate bodies from the carpenters. The huchiers, who then became exclusively what we should now call joiners and cabinetmakers, devoted their attention especially to all that required ornate treatment in carving, such as doors, windows, shutters and panelling, as well as chests, benches, bedsteads, chairs, dressers and wardrobes. These were largely fixtures and formed part of the permanent woodwork of a hall, or bedroom. The mouldings and other ornaments were carved directly out of the oak, and not applied.

Continue to: