256. Classification Of Trees

Description

This section is from the book "Bench Work In Wood", by W. F. M. Goss. Also available from Amazon: Bench Work In Wood.

256. Classification Of Trees

Classification Of Trees. There are in the United States nearly four hundred distinct species of trees, but the greater part of all the wood used in construction is taken from a comparatively small number.

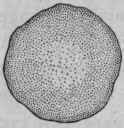

Trees are divided into two general classes known as exo-gens and endogens. The former includes all trees the trunks of which are built up by rings or layers, - the growth, therefore, being upon the outside. Endogenous trees increase from within, the new wood-strands being interspersed among the old, and causing cross-surfaces to appear dotted, as illustrated by Fig. 308, which represents a cross-section of the trunk of a palm tree. Old endogenous stems have the older and harder wood near the surface and the younger and softer toward the center. Examples of this class are found in palms, yuccas, and bamboos, and the character of their growth is well illustrated in the common cornstalk.

257. The Exogens are the timber-yielding trees, and since they furnish the woods useful in construction, they are the ones of special interest to the woodworker. They are subdivided into broad-leaved trees and needle-leaved trees, or conifers. Most of the broad-leaved trees are deciduous; that is, they shed their foliage in the autumn of each year. The needle-leaved trees are, almost without exception, evergreen.

Fig. 308

Fig. 309

258. Effect of Environment on the growth of trees is such as greatly influences their timber value. Trees which grow in the open, quite apart from other trees, acquire a shapeliness and beauty which is never equaled by those which grow in the thicket or forest, but the timber value of such trees is decreased by the presence of limbs, which branch from all sides of the stem, leaving but a short length of clean trunk from which clear lumber can be made, Fig. 309. A forest tree, on the other hand, finds light only at the top. The shade of the trees, which crowd it on every side, prevents it from putting out branches until it finds a level where it can reach out into or over their tops. A forest has in fact two floors, the first being the ground out of which the trunks of the trees spring, and the second, the floor of foliage where the tops of the trees branch, and crowd each other for room and light, and above which the occasional tree of unusual vigor rises and waves its lofty boughs. Between these two floors, a distance of from forty to more than eighty feet, extend the straight, limbless trunks of the trees which, like high columns, support the floor of foliage above. These straight, smooth trunks of the forest trees constitute the chief source of commercial timber. Fig. 310 shows a tree of forest growth as exposed to view by the removal of neighboring trees.

259. Broad-Leaved Woods vary greatly in structure and, therefore, differ widely in quality and use. In general, it may be said that they usually contain no resins and that their density, or weight, is great; they are usually hard and have a complex and irregular structure, and for these reasons are difficult to work; and they are likely to be of irregular growth and shape, having many branches, and, therefore, not productive of large logs or blocks which are free from knots. Some nail with difficulty and are in other ways unsuitable for use in general construction, but are better adapted to cabinetwork, the making of furniture and implements, and any other work which requires beauty of finish.

Fig. 310

Ash, basswood, beech, birch, buckeye, butternut, catalpa, cherry, chestnut, elm, gum, hackberry, hickory, holly, locust, maple, mulberry, sassafras, sycamore, tulipwood, and walnut are the principal American woods of the broad-leaved division. Of these the oak, ash, maple, beech, walnut, and poplar probably furnish the greater part of the commercial timber which comes from trees of this class. The general appearance of an oak, which may be accepted as a typical hard-timber tree, is shown by Fig. 309.

Continue to: