Drawing, Design, Lettering, Etc. Applied To Wood And Metal Work. Continued

Description

This section is from the book "Handcraft In Wood And Metal", by John Hooper, Alfred J. Shirley. Also available from Amazon: Handcraft In Wood And Metal.

Drawing, Design, Lettering, Etc. Applied To Wood And Metal Work. Continued

Design

It is a matter of extreme difficulty to lay down certain formula for this elusive subject. Certain sizes of objects have been decided by custom, tradition, and fitness for a definite purpose, but proportion can be varied, and in itself is an important element of design. Models or objects with a bold, decided outline demand a corresponding boldness of decorative detail, whilst the lighter forms of craftwork are best suited to a dainty rendering of detail. This guiding principle is well exemplified by a comparison of Elizabethan wood or metal work with Sheraton's work of the eighteenth century. In the former, heavy proportions demand the use of large mouldings and carving with a peculiar freedom of treatment, whilst Sheraton's elegant proportions have mouldings and projections reduced to a minimum, with decorative inlaid work, light and dainty in design, or painted ornament of a similar character. Another important factor in design is the material employed. Oak, a strong grained wood of coarse texture, requires a heavier treatment than satinwood; fine moulded detail in the former is obscured by the character of the material, and conversely, satinwood or ebony, having an even tone or colour, readily lends itself to lighter proportions and ornament. Colour values have again a material bearing upon the success of a design; rosewood, ebony, holly, and oak harmonize well in most combinations, as do also Italian or American walnut and purplewood, ebony, snakewood, and satinwood. There are numerous pleasing colour combinations possible in the use of naturally coloured woods alone, and the surest way to success is by experiment and careful observation with reference to harmony of colour. Ivory, tortoise-shell, and mother of pearl can be employed to advantage; the first material looks best when utilized in a dark groundwork for stencil effects. Tortoise-shell should be used in mass, and relieved by the use of silver or ebony, is very rich. The various varieties of pearl look best also in masses, with due regard to the beautiful colouring and lustre of the material. A study of historic work, and even prehistoric, cannot be too strongly urged; and to understand decorative craftwork, a study of history, customs, fashions, and politics is essential. The examples illustrated in various parts of the work show in some measure how traditional craftwork can be adapted to modern handcraft.

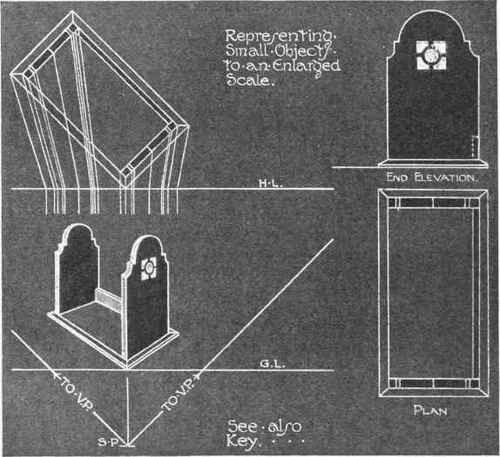

Fig. 7.-Method of representing small objects in perspective.

Lettering

First reference to handcraft deals chiefly with suitable imitation of printed characters on drawings. There are many excellent books published on this subject specially suited for students and teachers. Albrecht Durer type is well proportioned and tasteful in appearance; it has the added advantage of lending itself readily to geometrical construction, although this is not recommended unless a large exercise letter is being drawn. In one well-known antique book in the Victoria and Albert Museum at South Kensington, Albrecht Durer shows the constructions employed by him for the whole alphabet. Ancient Roman and mediaeval Italian is particularly good, and well repay study; this can be effected through the medium of old pictures, tablets, inlaid woodwork, and books.

For general handcraft purposes a square kind of lettering is best. Applied to working and scale drawings, headings in notebook and incidental descriptions, it is easy to space, and can with some little practice be quickly drawn. A good plan is to draw two lines parallel and about 1/4 in. apart. These are then converted into squares with a space of 1/16 in. between them. Such squares neatly filled with the letter (with the exception of I, which can be drawn with one stroke) give a precise and pleasing effect. Letters are then drawn in each square, and when spaced in this way completed words and sentences give a pleasing idea of good spacing and proportion. For class work, not more than one style should be adopted. The square lettering used upon many of the plates in this work can be reduced or enlarged in size according to the relative importance of the references, and have been found by the authors quite satisfactory for class work.

Figs. 8 to 12 of this chapter are some reproductions of artistic metalwork that have been made for various purposes and in different metals, and which in some cases are based on traditional styles. It will at once be seen how important are drawing, design, and lettering, in conjunction with mechanical processes and the knowledge of materials. They are examples of work that can be done by good craftsmen, and are modern. They show how material must govern design, and if this kind of work is to be maintained, it is evident that design drawing and lettering should be practised in conjunction with the actual work. In many cases the craftsman must be an artist. Teaching design in the abstract is of little use. It is useless to make a fine design for a wrought-iron entrance gate, and when the working drawing is made, and the work comes to be executed, it is found that it cannot be made owing to its prohibitive cost (caused by the length of time required to make it), or its faulty construction, or the impossibility of making and fixing in the metal required the forms as designed. The designer of metalwork must have knowledge of materials and technical processes, as well as of symbolical and conventional ornament. Many kinds of drawing, such as the drawing and colouring of plants, geometrical drawing, including development of surfaces, drawing with chalk, crayons, or charcoal on brown paper, or with charcoal, blue or red pencil on white paper, especially if of a large size or to a large scale, are useful in metal-work. The working out of workshop drawings from small coloured sketches is excellent practice, as it brings forward many points often overlooked in the small sketches. The working drawings should consist of full-sized drawings (where practicable) of each particular part and detail with the sizes in figures, as well as the constructive details (joints, etc.), which are most suitable for that particular part, and should show the name of the material to be used. If cast and turned work enter into the design, there would be the necessary patterns, core prints, core boxes, etc., to be drawn, showing the necessary allowances for shrinkage, turning, and fitting together, and the pieces that sometimes have to be added (and afterwards removed) for holding the work. Often during the manufacture, patterns or designs arise which in themselves can be utilized as decorative features, e.g. the rivets which hold the raised piece of metal on the finger plate (p. 67); only three are necessary, the rest could be dummies, but they form a decorative feature. The laps on the tin box on p. 69 are decorative as well as necessary.

Continue to: