Florence. Part 8

Description

This section is from the book "Florence - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

Florence. Part 8

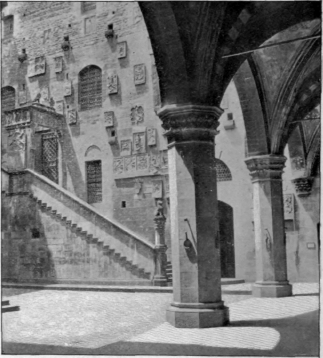

The Staircase.

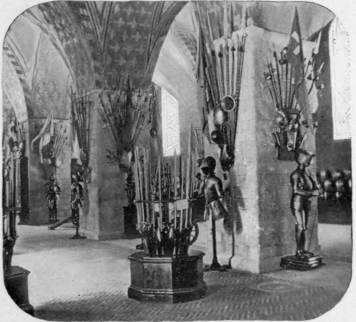

The Armory.

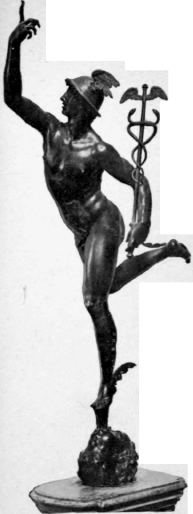

Climbing the ancient staircase, up which so many had preceded us, we entered one of the halls of the Bargello. At present, the building is neither a palace nor a prison for state criminals, as was the case in the sixteenth century, but serves as a most interesting National Museum. Among a multitude of antique bronzes here displayed, the traveler turns to one, as to an old and highly prized acquaintance. It is the Winged Mercury of John of Bologna. What an unfailing source of pleasure this inimitably graceful figure is! Even the poorest model that we see of it cannot completely lose the spirit of exultant energy and swift activity breathed into it by its creator. It is the ideal embodiment of fleetness and irrepressible youthful vigor. The sense of rapid movement through illimitable space that sometimes comes to us in dreams, finds its supreme expression in this messenger of the gods who spurns the earth with winged foot, impatient of delay. Yet though his progress is arrested, he has the absolute repose of perfect art, and causes us no restlessness because his flight is thus delayed. Monarch of motion, he stands serenely poised in an expectant attitude, which needs but the dissolving of some subtile spell to send him springing forward on his joyous mission.

The Museum Of The Bargello.

The Winged Mercury.

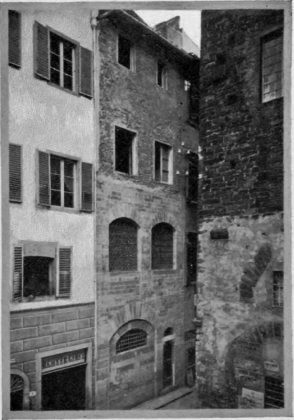

Leaving this National Museum, as I was passing through one of the oldest and narrowest streets of Florence, I saw above the doorway of a tall stone house a marble tablet. Approaching it, I read with interest the words : "In this house, in 1265, was born the divine poet, Dante." The structure has been recently rebuilt, and almost ruined as a genuine relic of antiquity, but interest in the site it occupies can never die; for, aside from its association with the author of the "Divine Comedy," it became, two hundred years after Dante's death, a kind of club where statesmen, artists, wits, and scholars loved to congregate, among them being Michelangelo and Benvenuto Cellini. The tablet on the house of Dante is by no means an exception here. Florence shows the love she cherishes for her illustrious children by marking with inscriptions the historic buildings which have been illumined by their genius. Accordingly, the glory of antiquity greets us continually, and almost all the bridges, streets, and stately edifices of this Tuscan city have some associations with great men or deeds that thrill us by their stirring memories.

Dante's house.

"'Tis the Past

Contending with the Present; and in turn

Each has the mastery".

In the Via Ghibellina stands the house of Michelangelo, which, as recently as 1858, was still owned by one of his descendants, who then bequeathed it to the city of Florence. It is intensely interesting, because it brings us nearer to the human side of the great genius than his Titanic works can ever do. So forceful, grand, and awe-inspiring are his colossal statues and frescos, that their creator seems at times almost a demigod; and it is, therefore, with a feeling of relief that we here see and touch, in addition to the easel, palette, and brushes of the artist, the armchair, walking-stick, and slippers of the man.

The bust of Michelangelo, in the National Museum of Florence, reveals a face upon which thought, care, pain, and bitter struggles with the world have left deep traces; a face, too, which had been disfigured for life by the blow of his envious fellow-student, Torregiano. Yet it is kindly, notwithstanding its severity and sadness; and although its features are those of the cold and reserved sculptor, before whose gray hairs even Pope Julius II. rose in reverence, and in whose presence the Grand Duke Cosimo stood with uncovered head, they are also the lineaments of the man who nursed his aged servant in sickness with the tenderness of a mother and slept, without undressing, upon a couch that he might be ever near to render him assistance.

Dante.

Continue to: