Examination Of Bone Marrow in Leukemia Diagnosis

Description

This section is from the book "Early Detection And Diagnosis Of Cancer", by Walter E. O'Donnell. Also available from Amazon: Early Detection And Diagnosis Of Cancer.

Examination Of Bone Marrow in Leukemia Diagnosis

1. It is always desirable and often imperative to have at least one base line marrow study. As will be noted below, there are times when the diagnosis of leukemia can be made only by means of bone marrow examination. However, this is not always essential, since the diagnosis can often be made with considerable assurance on the basis of the clinical findings and examination of the peripheral blood. Particular circumstances must decide just how important a bone marrow examination is.

2. Knowledge of the state of the hone marrow has two major uses:

(a) Differential diagnosis. In certain cases of so-called aleukemic or subleukemic leukemia, the total white blood cell count may be normal or low and the differential smear may be relatively normal as well. Under these circumstances bone marrow aspiration is crucial to the diagnosis. Also, in resolving diagnostic dilemmas posed by leukemoid reactions, aplastic anemia, so-called leukolym-phosarcoma, etc., knowledge of the state of the marrow may play a key role.

(b) Following the course of the disease, treated or untreated; This is particularly true in acute leukemia. Premonitory changes in the marrow may herald the onset of a remission or relapse some time before the clinical picture changes, allowing the therapist to institute, change, or discontinue treatment without having to wait for the latter to develop.

3. Marrow aspiration can be done from any one of several bony sites. The choice is purely one of personal preference. The two most commonly used are as follows:

(a) Sternum

(b) Iliac crest

4. In either site the technique is essentially the same. For the iliac crest the procedure is as follows:

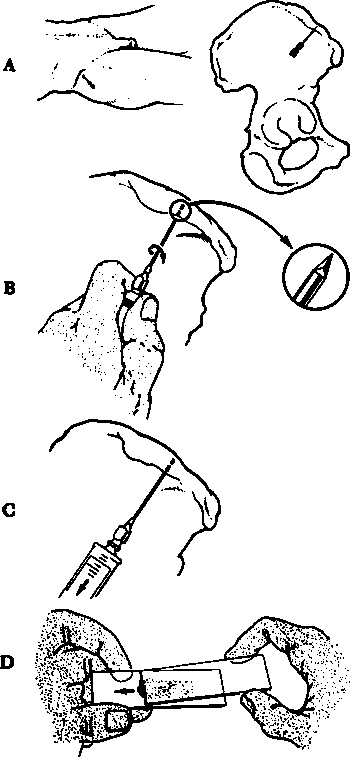

(a) With the patient in a supine position, infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and periosteum of the selected site with 1% procaine. Insert a bone marrow aspiration needle (such as a Turkel) into the ridge under the anterior lip of the iliac crest (Fig. 81, A)

(b) Use firm, gentle, twisting pressure until the needle enters the marrow cavity. This is indicated by a sharp decrease in resistance (i.e., the needle "gives"). Attach a standard 10 to 20 c.c. (ml.) syringe. Test the entry by aspiration (blood in the end of the syringe) (Fig. 81, B).

(c) Aspirate less than 1 ml. to avoid dilution of the marrow with blood (Fig. 81, C). Marrow elements can be identified as small yellow particles.

(d) Prepare several slides in standard blood smear fashion (Fig. 81, D). Stain with Wright's or Giemsa's stain.

(c) The clot left in the syringe should be put in formalin and sent for pathologic examination.

With the patient in a supine position,infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tissues and periosteum of the selected site with 1% procaine. In-sert a bone marrow aspiration needle (tsuch at a Turkel) into the ridge under the anterior lip of the iliac crest.

Use firm, gentle, twitting pressure until the needle enters the marrow cavity. This is indi-cated by a sharp decrease in resistance (i.u., thu needle "gives"). Attach a standard 10 to 20 c.c. (ml.) syring. Test the entry by aspiration (blood in the end of the syringe).

Aspirate less than 1 ml. to avoid dilution of the marrow with blood. Morrow elements can be identified as small yellow particles.

Prepare several slides in standard blood smear fashion. Stain with Wright's or Giemsa's stain. The clot left in the syringe should be put in formalin and sent for pathologic examination.

Fig. 81. Technique of bone marrow aspiration (iliac crest).

Other Studies

Additional studies may be done to confirm the diagnosis or to evaluate the nature and extent of involvement of almost any tissue or organ. Obviously the list of possible studies could be extremely long. Some of the more commonly ordered ones include:

1. Urinalysis; also urinary urobilinogen determination

2. Blood studies

(a) Coombs' test (direct and indirect) and serum bilirubin and reticulocyte count for possible hemolytic component to the anemia

(b) Heterophile agglutination test to rule out infectious mononucleosis

(c) Liver function studies

(d) Leukocytic alkaline phosphatase determination to differentiate leu-kemias (low levels) from myeloid metaplasia and leukemoid reactions (high levels).

3. X-ray studies to rule out involvement of the following:

(a) Chest

(b) Bones

(c) Kidneys

(d) Gastrointestinal tract

4. Lumbar puncture with examination of cerebrospinal fluid (cell count, chemistries, cytology, enzyme studies) to evaluate neurologic problems

Leukemoid Reactions

The possibility of a leukemoid reaction must frequently be considered when leukemia is suspected. The hematologic picture of leukemia can be simulated, often to a striking degree, by a rather large variety of conditions, ranging from the benign and innocuous to the malignant and fatal. Not only may the blood picture suggest the mistaken diagnosis of leukemia because of a high white blood count and/or abnormal smear, but the condition causing the leukemoid reaction may present clinical manifestations paralleling those expected in leukemia. If one is aware of the possibility, the distinction between leukemia and a leukemoid reaction can usually be made without great difficulty. There are times, however, when such a differentiation may tax the resources of even the most astute clinician. The need for caution and precision in making a diagnosis such as leukemia is obvious.

A partial list of conditions causing leukemoid reactions as summarized by Wintrobe are:

1. Infections presenting pictures resembling the following:

(a) Myelocytic or myeloblasts leukemia - pneumonia, meningococcus meningitis, diphtheria, and tuberculosis.

(b) Lymphocytic leukemia-whooping cough, chickenpox, infectious mononucleosis, infectious lymphocytosis, and tuberculosis.

(c) Monocytic leukemia-tuberculosis.

2. Intoxications-eclampsia, severe burns, and mercury poisoning.

3. Malignancy, especially with bone metastases; also multiple myeloma, myelosclerosis, and Hodgkin's disease.

4. Severe hemorrhage-sudden hemolysis of the blood.

The criteria which are usually interpreted as favoring the diagnosis of leukemia are as follows:

1. Marked immaturity of the white blood cells

2. Evidence of other disturbance in the blood picture, including:

(a) Anemia

(b) Thrombocytopenia

3. The following clinical findings:

(a) Hepatosplenomegaly

(b) Lymphadenopathy

(c) Hemorrhagic manifestations

(d) Pallor

4. Observation of the course of the disease (i.e., persistence of the hematologic findings and appearance of confirmatory clinical evidence)

Continue to: