Malta. Part 7

Description

This section is from the book "Malta - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

Malta. Part 7

Where Knights And Moslems Fought.

John Be La Valette.

Nevertheless, although St. Elmo had thus fallen, Malta itself was far from being subdued. "If the child has been purchased at so terrible a price," exclaimed the Turkish commander, "what will the parent cost us?" For, in fact, in the siege of St. Elmo alone the Turks had lost eight thousand men, while of the Christians only fifteen hundred had been slain, one hundred and thirty of whom were members of the Order. The story of the conflicts which thenceforth occurred is one of the most exciting ever chronicled. Each day gave rise to some new tragedy. Now it would be a poisoned water supply, whereby eight hundred Moslems died in agony, or a terrific struggle between Mohammedan and Christian swimmers; the former, armed with axes, trying to cut the chain stretched by the Knights across the upper harbor, the latter defending it with daggers - a strange amphibian combat, as of sea monsters, the water meantime being dyed with blood. Or now all eyes would turn with mingled horror and excitement to where the Turks were making one of their assaults with scaling ladders; while, to repel them, the defenders pushed off from the parapets enormous sharp-edged stones, which struck the assailants struggling to ascend, and crushed them to the earth, bruised, bleeding, often killed outright. Still worse than this was the effect produced by pouring on the climbing Moslems boiling pitch, which caused excruciating agony in those on whom it fell; while yet another hideous device for beating back the foe was casting down upon them iron hoops, which had been previously wrapped in cotton soaked in oil and sprinkled with gunpowder, and were ignited at the moment of their fall. These were thrown down in such a way as to enclose two or three men together in a blazing belt, which, ere it could be thrown off or extinguished, often burned them fatally. Such were the fearful scenes continually enacted during this memorable struggle.

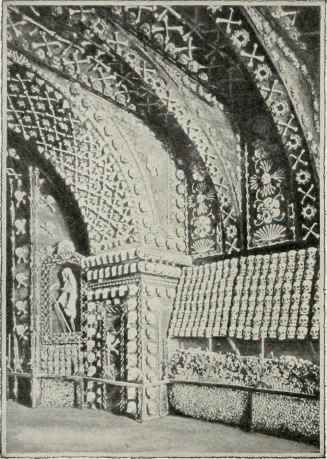

The Trophies Of Death, Valetta.

As tidings of the siege reached Europe, all Christendom became intensely interested in the issue, and prayers were offered in the churches everywhere for the deliverance of Malta. So great, however, was the discord in the "Concert of Nations" that it was only in the month of September that a small relieving force of Europeans reached the islands. Yet, though the long delay of its arrival had almost proved fatal to the enterprise, its coming really turned the scale, and caused the Turks, already weary and disheartened, to retreat precipitately to their ships and sail away. They were a miserable company of barely fifteen thousand, out of the forty thousand men who had originally left the Sultan's capital to subdue the Knights. Of the nine thousand Christian combatants who had seen the opening of the conflict, only six hundred stood unwounded at its close.

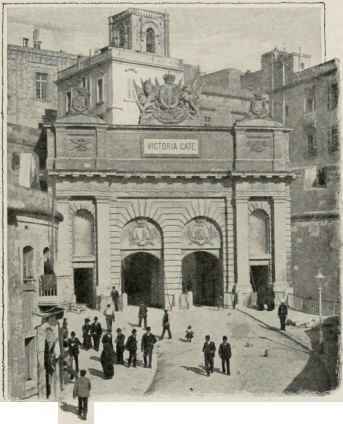

The Victoria Gate.

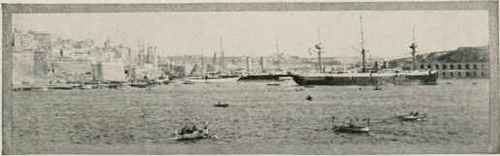

Valetta is vivacious. Despite much poverty, it shows more smiles than tears. On Maltese faces seems to shine a bright reflection of the omnipresent sea, which in this clime is rarely sad ; but, on the contrary, as if rejoicing to possess these islands, which it holds so lovingly upon its breast, forever sparkles in the sunlight, dimples with the breeze, laughs with the rippling surf, or shouts among the breakers romping on the shore.

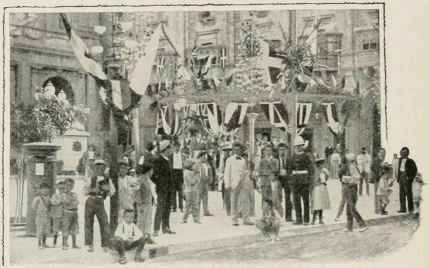

A Festival In Valetta.

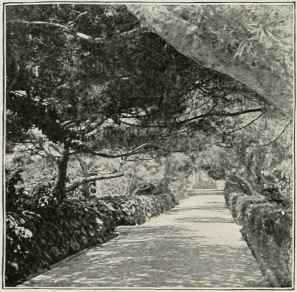

In The Botanical Gardens.

Malta has been called arid, but fifty fountains make Valetta musical, and quench its thirst. Moreover, in the springtime, it might well be named the home of Flora. Then all the second stories of its yellow houses are ablaze with color. Pinks, tulips, pansies, violets, and roses decorate the balconies, as if the latter were proscenium boxes at a floral carnival. Have you a buttonhole bouquet? If not, you will be out of fashion. Patronize, therefore, at the first street corner one of the gaily tinted kiosques, whose pretty tenants offer flowers and fruits, as well as newspapers. I found it best to buy a boutonniere at once, when starting for a morning stroll, since it was never more than half an hour before my coat was thus adorned. I could not go a block from the hotel before a Maltese flower girl would beg me not to pass her by; and even if I steeled my heart against the first six suppliants, I would surrender to the seventh, perhaps too hypnotized by her appealing eyes to count my change. The Strada Reale is a street of surprises. I envy one's sensations who first confronts its picturesque perspective. In the mere matter of light and shade it gave me an impression I had never elsewhere gained. The street runs very nearly north and south, and is at regular intervals intersected by side thoroughfares, through which the rising or declining sun pours parallel streams of yellow splendor. Hence, as I looked along this royal highway, it seemed to be divided into sections by a series of transparent curtains, whose solar tissues were so fine that they hid nothing back of them, but stretched across the street like screens of volatilized gold. So rich and varied is the architecture of the Strada Reale that, even after several tours of inspection, I never failed to find there some historic portal, graceful balcony, or fine armorial bearing of the Knights, which had till then escaped my notice. The color of the buildings is a delicate cream, which rims, in beautiful relief, the long and narrow roof of cloudless blue surmounting every street.

Continue to: