Principles Of Design Illustrated By Historic Costumes

Description

This section is from the book "Clothing For Women: Selection, Design, Construction", by Laura I. Baldt. Also available from Amazon: Clothing For Women: Selection, Design, Construction.

Principles Of Design Illustrated By Historic Costumes

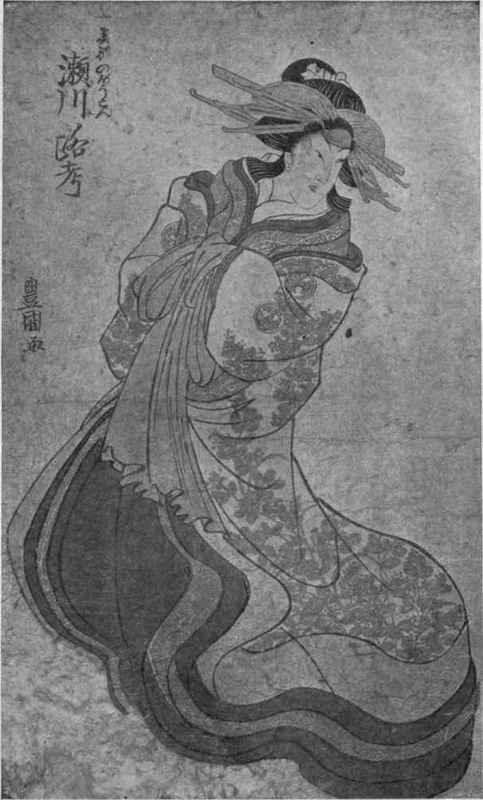

The two-fold aim of clothing design is to express the beauty of the human form and make the garment a work of art, independently of the form on which it is worn. The first ideal is based on the structure of the body for the lines of the design, and the articulation of forms for the subordinate parts. The Greek costume shown in Fig. 23 illustrates this. The two large divisions of the garment cover the torso and the limbs and hang from the natural supports, the shoulder and the hips. The great charm of the Greek drapery is in its subtle suggestion of the contours of the body. Ancient Japanese art furnishes examples of design on its own account as the aim of the costume. Much rhythmic beauty of line and mass pattern is found in the old Japanese print (see frontispiece). It has an exquisite evolution of flowing lines and subtle variety in the relation of the masses. These two illustrations make clear the two ideals which may inspire a design. We believe the first offers a greater possibility for beauty in dress, but we ought to be able to recognize good design from the other angle.

Rhythmic beauty of line in the costume illustrated in this old Japanese print by Toyokuni. (See page 61.)

Lines may be said to be only the edges of masses. Composition should have both straight and curved lines, the former giving unity, the latter variety. Fig. 24, the archaic Greek dress, shows an interesting combination of straight and curved lines. Straight lines convey a feeling of power, dignity, stability, calmness, nobility. Curves are the life and joy of an arrangement. Restrained curves are always beautiful; curves may be used with freedom on clothing to be worn on occasions of gaiety. Simplicity in masses is an element of good design. All decorative detail must be kept subordinate, and should be consistent in feeling with the idea of the whole.

In the outlines of the costumes, in Figs. 25, 26, and 27, the point of view of the application of clothing design to the human form is found in all the designs from the earliest time to about the sixteenth century. Then there was adopted a decorative structural contour (1500-1700 A.D., Fig. 26) which lasted until the early 1800's, when the classical Empire became the fashion. After this there was a return to the preceding type, which held its own up to about 1870, when there was a change, and a long period of inadequate attempts toward a silhouette ensued, 1870-1900. Within the last few years we achieved an approach to a contour of rational beauty, but this may be short-lived for, according to present commercial standards, fashion must be ever changing. In the clothing of the woman of the Bronze Age (Fig. 25), we find simple basic elements of structure, with consistent ornaments worn at natural articulations. The simple lines of the garment are combined with a strong, simple, decorative detail. The Egyptian costume in Fig. 25, in a more elaborate way, repeats the structure of the body, and shows unity of line, while variety is given in the cape-like arrangement and the lines of the girdle. How many centuries has the Greek drapery held first place in the realm of beauty! In the Greek costumes (Figs. 23 and 25), the lines perfectly echo the grace of the body, while simplicity predominates in the straight lines, giving a sense of nobility. The costume of 1000, Fig. 25, is typical of several centuries, for fashions did not change in hundreds of years then as they do in a few weeks to-day. The general contour, which has an obvious relation to the body, is good,and the design depends upon the long simple lines to give it dignity. The inner sleeve and the girdle furnish the variety. The costume of 1100, Fig. 25, does not differ structurally from that of 1000 except in the sleeves. The beautiful calm lines of the mantle add to the beauty of the whole. The structural outline of the year 1240 is much the same as that of 1339 (see Fig. 25), but there is a new element in the design, the chasuble or jacket effect conforms to the line of the torso and the curves give variety. The stately gown of 1339, Fig. 25, introduced more features of design, in contrast of line in a horizontal support of the mantle and a rhythmic movement in the curves. Unity is emphasized by the long mass of the front and the outline of the mantle. Fig. 25, 1370, shows a beautiful feeling for structural form and more imagination in the decorative detail. The shape of the neck and the bottom of the overgarment repeat each other, while the design on the hips lends variety. In 1440, Fig. 26, a new structural mass is seen - the division at the bust line, the horizontal line at the knees, repeated at the belt, is good, while the pointed waist is echoed in the tall henin. The example of 1500, Fig. 26, belongs to the class of costume that has an artificial or decorative structural basis. The upper part follows the body, but the skirt has no relation to human form. There is unity in the character of the masses of the sleeves and the skirt and collar, with the point of the bodice. The jewelled ornament carries the eye to the face of the wearer. Fig. 26, 1600, shows the farthingale, or wheel, effect. Here the result is almost pure design. The big masses are harmonious, and are decorated by the radiating lines of the skirt, farthingale, and collar. Unity is established by the center point of the bodice. The decorative treatment of the sleeves and the bodice is in harmony with the whole. The shoulders and face appear as a center of interest. The second costume (1600) is not quite so varied but has greater simplicity. The long lines of the front give dignity. Note how the curves seem to grow out of each other. Fig. 26, 1700, is a good example of radial unity and line, which conforms to the general contour, with variety in the decorative details. The second costume, 1700, has a structural form, the parts of which harmonize, also the sleeve with the body of the garment. The long lines at the back are very beautiful. The third costume (1700), Fig. 26, is a good design in a period of exaggeration. The general contour is artificial, but the smaller parts are all in keeping, from the round neck to the ruffled scallops of the skirt. The lines of the back seem to suggest the form slightly. The Empire costume; Fig. 26, of the first quarter of 1800, changes again the form of the big masses. The smaller parts have a charming relationship of unity and variety, the long lines cling and suggest the body. The costume of 1831, in Fig. 27, is a reversion to the artificial silhouette. In the subordinate parts we see unity in the shapes of the masses. The wrap worn in 1846, Fig. 27, has a pleasing design in the rhythm of the curves. Fig. 27, 1854, is an excellent example of rhythmic arrangement by the repetition of the smaller parts. Its variety of line is consistent with the occasion for which the dress was designed. Fig. 27, 1866, shows unity in the big masses and radial lines. The costume of 1879, Fig. 27, is an attempt to return to the natural silhouette, but what a failure! The garment is an example of very poor design, without unity in line or mass, and much unrelated in variety. Fig. 27, 1887, has a perfectly arbitrary silhouette, and is without even decorative unity. Fig. 27, 1900, is an improvement over 1887, but is still not successful. The lines have a certain uniformity of character that are not beautiful. In the costume of 1909, Fig. 27, there is a good structural feeling in the general form and in the parts; through unity, variety, and balance, it approaches beauty.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Fig. 23. - Greek costume.

Fig. 24. - Archaic Greek costume.

Bronze Age

Grecian

Egyptian

A.D.1370

A.D.1700

A.D.1831

A.D.1879

FIG. 27. - Principles of design illustrated by outlines of historic costumes.

Continue to: