Less Common Or Specific Applications Of Circular Saws To Large Works. Part 5

Description

This section is from the book "Turning And Mechanical Manipulation", by Charles Holtzapffel. Also available from Amazon: Turning and Mechanical Manipulation.

Less Common Or Specific Applications Of Circular Saws To Large Works. Part 5

Crown-saws, as large as 5 feet diameter and 15 inches deep, constructed somewhat alter the manner of fig. 797, arc employed

Messrs. Esdailcs' saw-mills. The three or four pieces of steel thenconstituting the hoop, are rivetted to the outside of a strong ring, and very carefully hammered, so that the plates exactly constitue one continuous cylinder; although the ends of the plates arc not united, but simply make butt-joints. The ring is fixed to the surface-chuck of a kind of lathe-mandrel, by means of hook-bolts h, and the work is grasped in a slide-rest, which traverses within the saw, and parallel with its axis.

The saws of about 2 feet diameter are used for cutting the round backs of brushes b, and the larger saws are employed for felloes of wheels d, and similar curved works. If the wood is applied obliquely, the piece also becomes oblique, in the manner explained by the diagram c, which represents the sloping and hollowed back of a chair thus produced. It is, however, much more usual to saw curvilinear works of the kinds referred to, with the felloe or pit-turning saw (see page 707), the chair-maker's and wheelwright's saw (p. 725), and the turning sweep, or bow-saw (p. 728), the respective applications of which have been already noticed at the pages referred to.

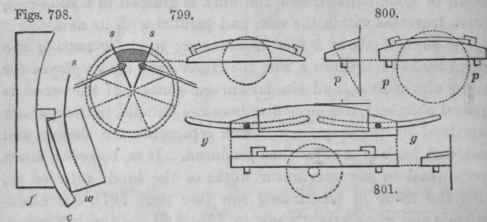

Mr. Trotter proposed for curvilinear sawing, the employment of a saw-plate s, fig. 798, which instead of being a flat plate, as usual, was dished as the segment of a large sphere. The fence f, which was made as the arc of a circle, had a conductor c, to receive the work w; the circular fence was attached to a three-bar parallel rule, so as always to keep the curvatures of the fence, conductor, and saw, which were equal, truly parallel with each other. The construction of the spherical saw-blade is difficult, and its advantage questionable, especially as the edges of the pieces when left from the saw, would be curvilinear in width as well as length, or part of a spherical surface, of the same radius as the saw. This form is seldom required in the arts, and its conversion into the simple arch-like form with square edges (proposed to be approached by inclining the work), would fully cancel the intended economy of the spherical saw, which is however curious, as one of the links in the chain of contrivances under consideration.*

* Rees's Cyclopaedia, art. "Machinery for Manufacturing Shipe' Blocks." - Encye. Metropolitan, vol. Mechanics, art. 376.

Much ingenuity has been displayed in cutting the curvilinear and bevilled edges of the staves of casks by circular saws. The late Sir John (then Mr.) Robinson, proposed many years back that the stave should be bent to its true curve against a curved bed, shown in two views in fig. 799, and that whilst thus restrained its edges should be cut by two saws s s, placed as radii to the circle, the true direction of the joint, as shown by the dotted circle representing the head of the cask. The principle is perfect, but the method has been found too troublesome for practice.

Mr. Smart cut the edges of thin staves for small casks on the ordinary saw-bench, by fixing the thin wood by two staples or hooks to a curved block, fig. 800, the lower face of which was bevilled to give the proper chamfer to the edges. One edge having been cut, the stave was released, changed end for end, and refixed against two pins, which determined the position for cutting the second edge, and made the staves of one common width. The curved and bevilled block, was guided by two pins p p, which entered a straight groove in the bench parallel with the saw.

This mode of bending was from various reasons found inapplicable to large staves; and these were cut, as shown in three views in fig. 801, whilst attached to a straight bed, the bottom of which was also bevilled to tilt the stave for chamfering the edge. To give the curve suitable to the edge, the two pins on the under side of the block then ran in two curved grooves g g, in the saw-bench, which caused the staves to sweep past the saw in the arc of a very large circle, instead of in a right line, so that the ends were cut narrower than the middle. Mr. Smart observes, that in staves cut whilst straight, the edges become chamfered at the same angle throughout, which although theoretically wrong, is sufficiently near for practice; the error is avoided when the staves are cut whilst bent to their true curvature.*

* Trans. Soc. of Arts, 1805. Vol. xxiv., p. 114.

Continue to: