Bohemia. Part 14

Description

This section is from the book "Bohemia - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

Bohemia. Part 14

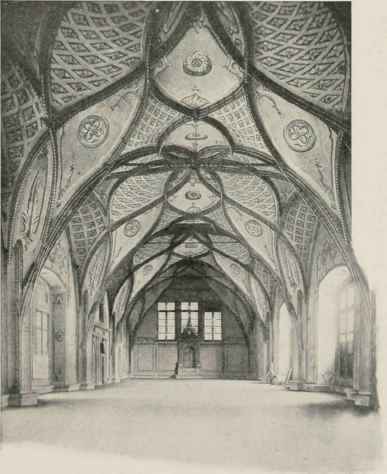

The Hall Of Homage.

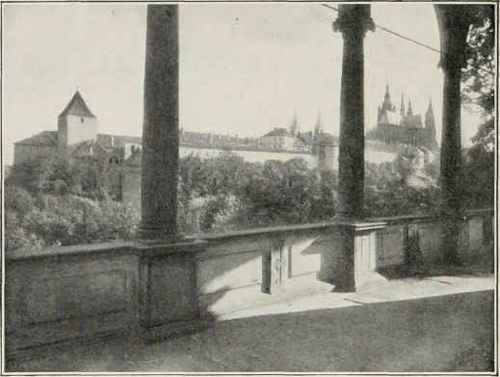

The Towers, From The Belvedere.

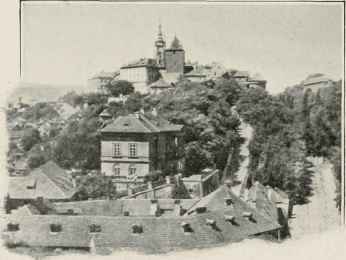

An Approach To Hie Hradsch1n.

The crown of Prague is the Hradschin. The jewel in that crown is its cathedral. From the old citadel's encircling walls the spires of that ancient church soar heavenward, like a stately flower from a sculptured vase. Its roots are deeply buried in the past, but its florescence is at hand. Two earlier Christian shrines preceded it upon this site, but of the present structure Charles IV. laid the cornerstone in 1344. Not yet, however, has it reached completion. Its growth has been retarded by the many tragedies in Prague's volcanic history. Bohemians love it for the woes it has endured. Great efforts have been made in recent years to finish it, and now the work is steadily progressing under the auspices of a society formed, in 1859, especially for that purpose. At present it consists for the most part of a noble Gothic choir with eight chapels; but, when completed, it will have a length of more than four hundred feet, and the old belfry which now surmounts it will be replaced by one whose height will probably exceed five hundred feet.

It is indeed expected that Czech architects will here produce a Gothic temple no less splendid and majestic than the minster of Cologne. The title of this ancient edifice is the Cathedral of Saint Vitus. Unfortunately, to a large proportion of the human race, the name of this illustrious saint suggests a nervous malady, and nothing more. Unless instructed otherwise, most of us certainly would suppose that he had been afflicted with the ailment which bears his name. It is, however, a supposition as groundless and erroneous as the belief that the Bohemians are gipsies. Saint Vitus was a Christian martyr, who suffered death under the Roman emperor, Diocletian. The legend in regard to him relates that when his father was about to visit him in prison to implore him to renounce Christianity, he found his son employed in dancing there with seven beautiful angels. This so surprised and dazzled him - as well it might! - that he was instantly struck blind, and could regain his vision only through the intercession of his son. On this account the saint became the patron of all dancers; and when, in the Middle Ages, the remarkable "dancing mania " spread through central Europe, Saint Vituswas the saint resorted to for cure. Hence, though the nervous trouble, now known as "Saint Vitus's dance," is not the same as that which then prevailed, it is sufficiently similar to it to have given the martyr's name to a disease, from which in all probability he never suffered!

It must not be supposed, however, that the association of Saint Vitus with the Prague cathedral had anything to do with that distressing malady. Six hundred years before the outbreak of the "dancing mania," Venceslas I., one of the earliest of Bohemian princes, received a relic of Saint Vitus, as the revered memorial of a noble martyr, and forthwith built a church for its reception, - a primitive forerunner of the great cathedral. The oldest and most sacred chapel in this Gothic sanctuary bears, in fact, the name of Venceslas, and dates from 1358. Its walls are most remarkable, being divided into two nearly equal sections, one above the other, the former being ornamented with rare mediaeval frescos, representing scenes in the lives of Christ and of Saint Venceslas; the latter being incrusted with a multitude of agates, amethysts, chryso-prases, jaspers, and other precious stones for which Bohemia is so renowned. The pointing of this glistening masonry was made with gold. The marble tomb of Venceslas stands in the centre of the chapel, and near it is his statue, together with his helmet and his coat of mail, for this old saint was evidently one of the Church militant.

The most impressive souvenir of all, however, is the ring of bronze fixed in the chapel's massive door. It is the one to which, in a small church in Alt Bunslau, Saint Venceslas clung desperately, when his brother Boleslav struck him the blows that caused his death. One cannot look upon this ring unmoved; for it is not alone a grim memorial of fratricide, but also of the fact that in that treacherous murder was embodied one of the last, ferocious efforts made by paganism to destroy Christianity. It was in the year 936. The Christian faith had hardly gained a foothold in Bohemia. Venceslas had accepted it. Boleslav rejected it. The people naturally were divided. No doubt the pagan brother had his partizans. But such a monstrous crime was, on the whole, repudiated. Christianity continued to make progress; the martyred Venceslas became a saint; and thousands kneel before his grave to-day to beg his intercession at the Court of Heaven. In one dim corner of this chapel is a secret doorway leading to a room where are preserved the old, historic crown and royal jewels of Bohemia. Formerly these were carefully guarded, twenty miles from Prague, in the magnificently situated, picturesque chateau of Carlstein, built by Charles IV. in 1348, and often occupied by him as a residence. Now it is more appropriate that these regalia should be treasured in the Hradschin, where they are deemed so precious, that the door of the apartment which contains them is locked by seven different keys, kept by as many dignitaries of the kingdom, among whom are the archbishop and the mayor of Prague. Will these insignia ever again be used? The heart of every Czech says "Yes!"

Continue to: